Photo of the South24 Research and Media Center, provided by the Meteorology and Civil Aviation Authority's Weather Forecasting Department in Aden.

Last updated on: 03-09-2025 at 4 PM Aden Time

|

|

Amid discussions on early warning mechanisms in Yemen, a fundamental question arises: To what extent can the current system—within its existing limitations—reach the most vulnerable groups, such as persons with disabilities, internally displaced populations, and marginalized communities?

Abdullah Al-Shadli (South24 Center)

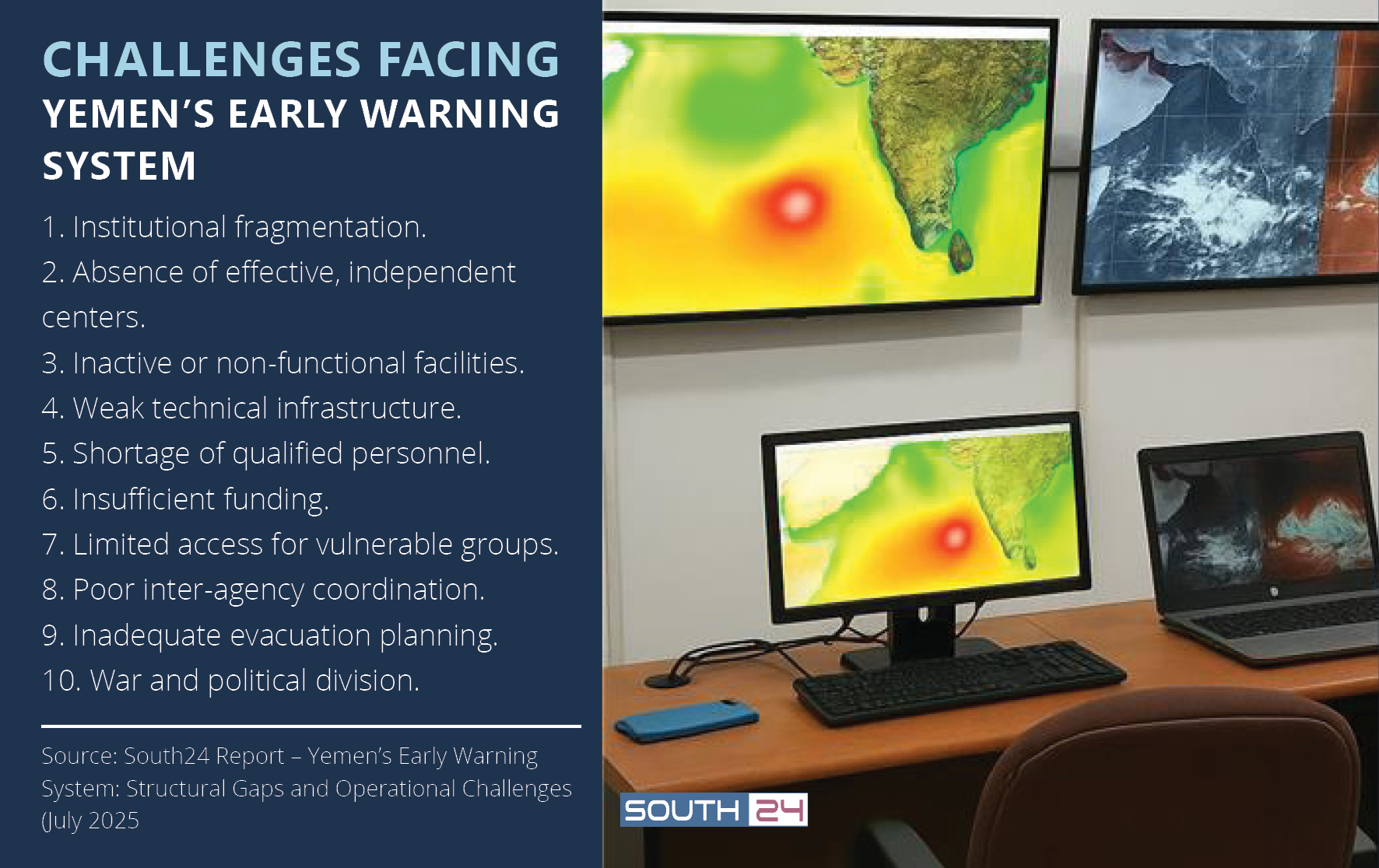

In a country weighed down by war and institutional breakdown, environmental risks are escalating at an alarming pace, while Yemen’s early warning system is either non-existent or, at best, barely operational. Despite the devastating disaster that struck Hadramout Governorate in 2008 -- declared a disaster zone after flash floods claimed dozens of lives and destroyed over 1,200 homes -- the country has witnessed no substantive progress in predictive modeling or emergency response infrastructure. The tragedy is almost repeated every year, amid growing extreme weather events linked to climate change.

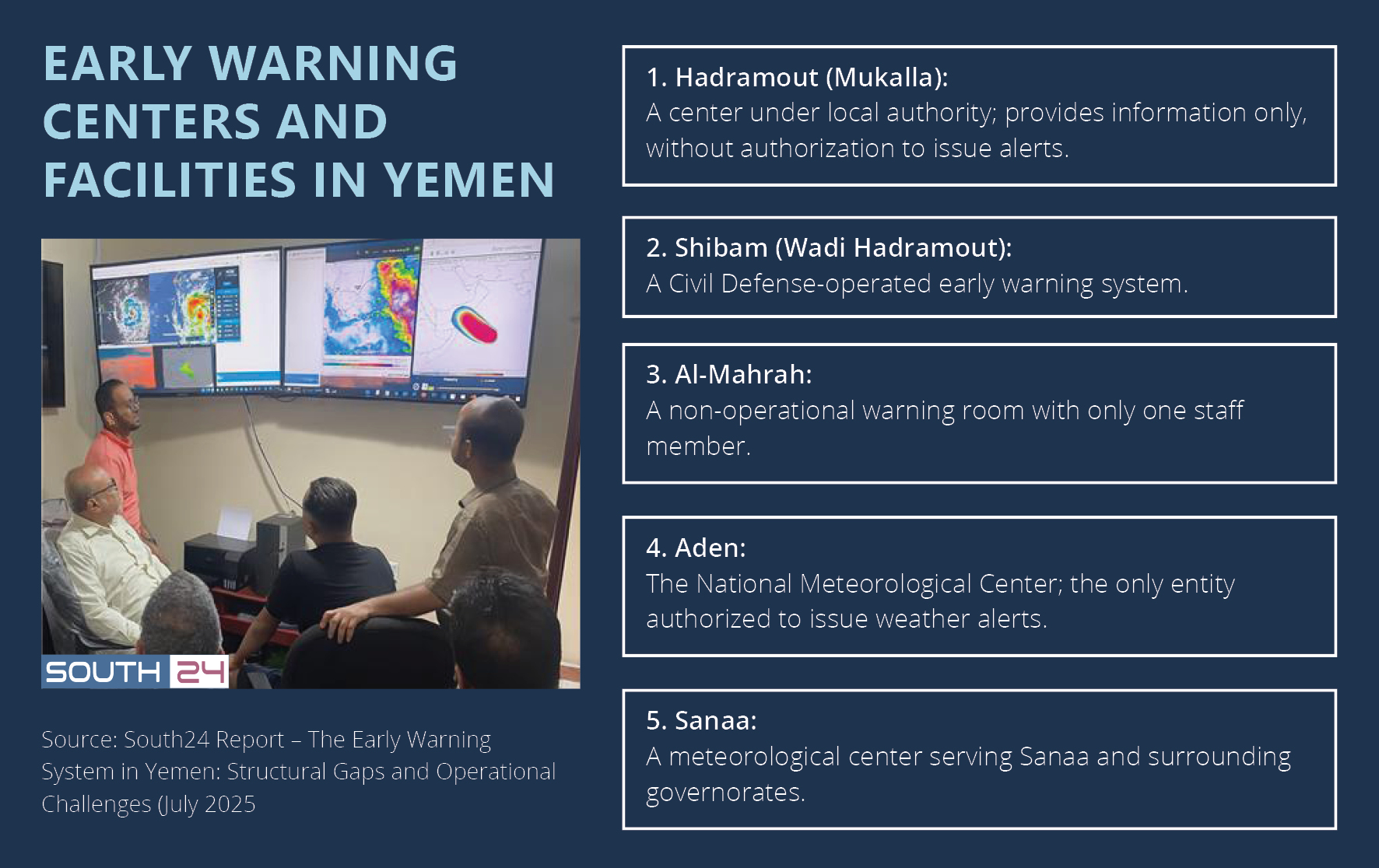

The distribution of early warning centers across Yemen reveals stark disparities in institutional structure, operational capacity, and administrative alignment—highlighting the absence of a cohesive national strategy, according to a survey conducted by ‘South24 Center’ in collaboration with meteorological officials and climate experts. In Hadramout Governorate, which is the most vulnerable to tropical cyclones, the early warning center falls under local government authority. It serves primarily as an informational entity that supports emergency planning but lacks the independent mandate to issue alerts or initiate immediate field-level interventions.

By contrast, the city of Shibam in Wadi Hadramout has a more advanced warning system affiliated with the Civil Defense Department. In Al-Mahrah Governorate, an early warning room exists but is non-operational, staffed by a single employee. Local promises to reactivate it have been hindered by staffing and equipment challenges.

Marib Governorate, home to one of the largest displaced populations in the country, lacks any early warning center altogether, despite stated intentions by the local authority to establish one in the future. This uneven distribution means that millions of people in the most vulnerable areas face disasters without protection or even the most basic forecasting capabilities.

According to Engineer Ali Jamal Batisir, Director of Weather Forecasting at the Civil Aviation and Meteorology Authority in Aden, Yemen has only one national center—located in Aden—that issues weather forecasts and alerts. These are then disseminated to relevant entities such as operations centers, the Prime Minister’s Office, and media outlets.

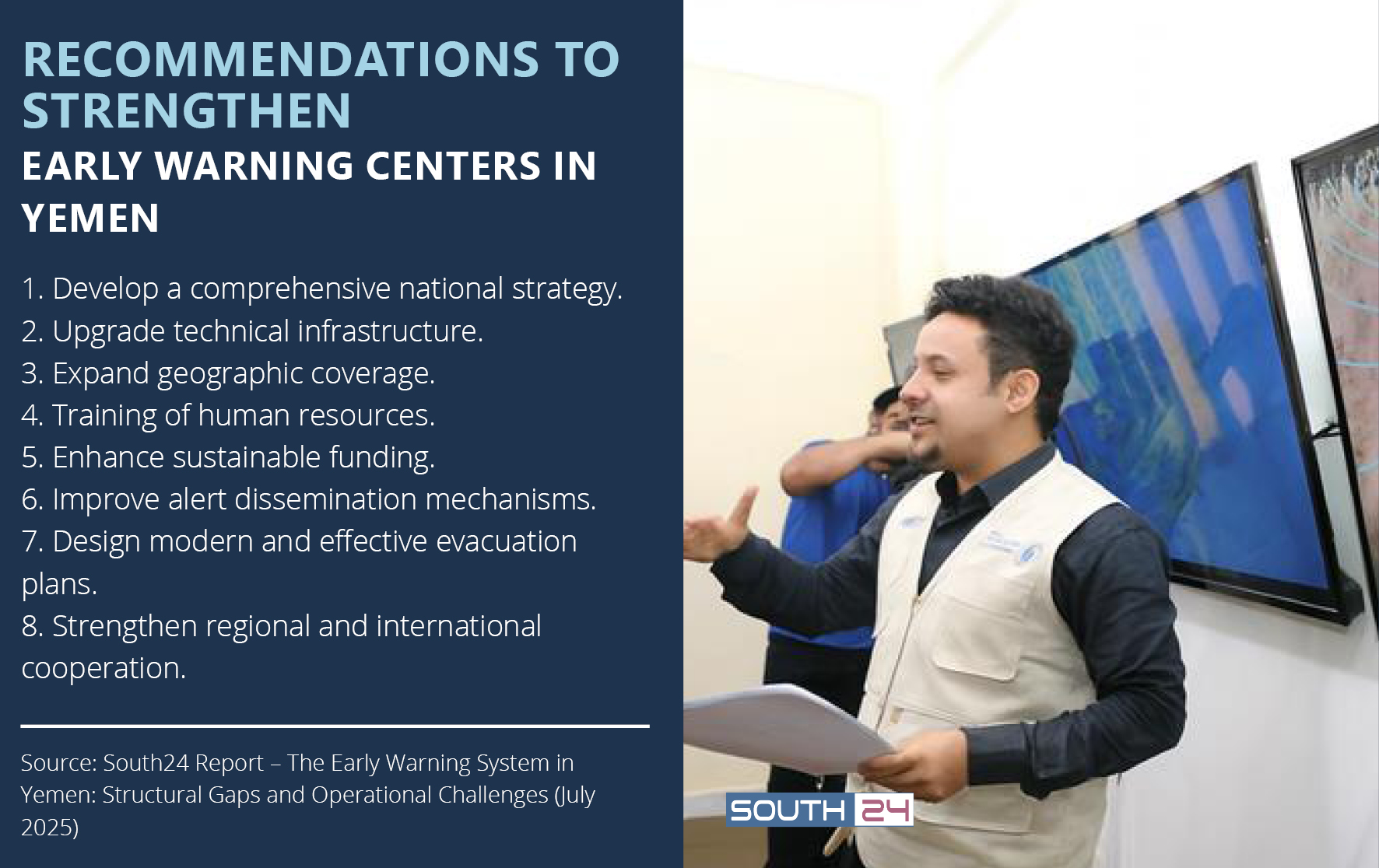

Batisir told ‘South24’ that establishing multiple regional centers would require substantial investment in technical equipment and advanced systems, as well as highly qualified personnel, given the sensitivity of the task and its direct impact on people’s lives and property.

He emphasized that the decision to issue or withhold alerts carries serious consequences that can either mitigate or worsen losses. He said that the authority operates a wide network of meteorological stations that enable continuous monitoring of weather conditions and help in issuing accurate forecasts. However, he warned that creating parallel centers without centralized coordination could lead to conflicting assessments and confusion among official bodies and the public.

Similarly, Engineer Mohammed Abdullah Al-Lisani, Director of Public Forecasting at the National Meteorological Center in Sana’a—under the unrecognized Houthi authorities—said that expanding integrated early warning centers across all governorates poses a major challenge. This requires specialized equipment and personnel trained at regional and international centers.

Al-Lisani added that human capital is the decisive factor in this equation, and it is not readily available under the current conditions. Nevertheless, he pointed to the possibility of establishing secondary centers staffed by specialists trained both theoretically and practically, to gradually expand community-level warning coverage.

Despite the political and institutional divide between Aden and Sana’a, both sides agree that current efforts are insufficient, and that broadcasting weather bulletins does not necessarily ensure their effective delivery to the target populations. Amid this backdrop, dozens of populated areas in Yemen remain exposed to cyclones, floods, and landslides—without effective warning systems, clear evacuation plans, or even properly functioning field monitoring equipment.

Field Fragility

Despite efforts by the National Meteorological Center and local authorities in some southern governorates, the situation on the ground reveals a significant gap between urgent needs and the response capabilities. In Hadramout, one of the most disaster-prone regions, the Meteorology and Early Warning Center began its modest self-funded operations in 2016, according to the center’s director, Engineer Abdulrahman Hameed. He told South24 that the center was officially inaugurated in 2021 with limited resources.

Hameed explained that the center initially consisted of a small office in an old building, with extremely limited equipment. They relied on a single monitoring station in the Fuwah area, which later ceased operations due to lack of maintenance and weak technical ability. Currently, the center depends on two meteorological stations in Mukalla and Al-Shihr, and participates in the global SYNOP network of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), which provides additional data that is manually entered into computers for analysis and forecasting.

Despite the modest resources, the center strives to ensure that weather alerts reach all segments of society, including the most vulnerable groups such as persons with disabilities, women, and children. Hameed stated that the center places great emphasis on this aspect, disseminating its bulletins through all available channels—from official media to social media platforms—as well as activating community committees in neighborhoods during emergencies to expand outreach.

He stressed that evacuation plans adopted by the local authorities include all population groups, with special priority given to the most vulnerable. He noted that during major tropical cyclones, such as Cyclone Chapala in 2015, successful evacuations were carried out according to well-structured timelines.

Engineer Ali Batisir added that weather alerts are delivered through multiple channels, including the official website of the Civil Aviation and Meteorology Authority, its social media pages, and a dedicated WhatsApp channel that sends bulletins directly to relevant entities. He pointed out that local radio stations play a key role in reaching remote areas, especially given the limited internet coverage.

Despite these efforts, Batisir acknowledged that achieving true inclusivity remains elusive. He stressed that technical and financial constraints, along with the lack of coordination with humanitarian organizations, hinder the effective delivery of bulletins to persons with disabilities and marginalized groups. He noted that national evacuation plans suffer from clear deficiencies and do not adequately meet population needs, explaining that, “the absence of strategic planning, shortage of resources, and security and economic challenges, all undermine the effectiveness of disaster response.”

In Sanaa, Engineer Mohammed Al-Lisani expressed similar concerns, noting that the meteorological sector’s efforts are hampered by limited resources and a lack of awareness among some officials about the importance of weather forecasting in saving lives and property. He said the sector is doing its best to ensure alerts reach various governorates, but stressed that responsibility does not lie solely with the meteorological authority—it must be shared by all government entities involved in disaster management.

Al-Lisani affirmed that serving persons with disabilities is an issue that requires systematic integration into the meteorological sector’s future strategies. He promised to convey the related recommendations to the sector’s senior leadership and also stressed the need to enhance coordination with local entities to ensure alerts reach all segments of society without exception.

Marginalized Groups and Displaced Populations

Amid ongoing discussions about early warning mechanisms in Yemen, a fundamental question arises: To what extent can the current system—within its existing limitations—reach the most vulnerable and marginalized groups, including persons with disabilities, internally displaced populations, and socially excluded communities? This concern is especially pressing given the widespread presence of informal displacement camps on the outskirts of cities and in flood-prone areas, where media coverage is virtually absent and basic services are lacking.

Dr. Nabila Al-Qadri, a Yemeni climate and environmental expert, expressed deep concern over the limited inclusivity of the current system. Speaking to ‘South24’, she said: “I firmly believe that current early warning bulletins do not sufficiently reach all segments of society, especially the most vulnerable—marginalized groups, the poor, and persons with disabilities—many of whom have been further impacted by the conflict.” She explained that these groups often fall outside any formal institutional framework, leaving them exposed to compounded risks without prior warning or assistance.

Al-Qadri noted that hundreds of thousands of displaced people live in areas ill-equipped to withstand disasters, such as makeshift camps built in low-lying areas or along flood channels. “They often do not receive alerts in time and lack the logistical capacity for immediate relocation or evacuation,” she said.

To overcome this gap, Al-Qadri proposed activating direct communication mechanisms that include coordination with local district authorities, engagement of community leaders, camp managers, and humanitarian organizations that work directly with these populations. She emphasized that involving these local actors could enhance the effectiveness of alert delivery and accelerate response during critical moments.

While acknowledging the existence of some awareness bulletins issued by meteorological centers and disseminated via media and social media platforms, Al-Qadri argued that these efforts remain limited in scope and impact. She stressed the need for them to become “part of a comprehensive and binding national plan”, particularly regarding special groups such as persons with disabilities who require alternative or sensory-adapted communication tools.

She explained that current evacuation plans are general in nature, and lack clear implementation mechanisms that take into account the realities of vulnerable groups. “The existing plans treat the affected population as a single mass, without tailored tools or procedures for those requiring additional care,” she said. Protection for these groups often relies on tribal customs and community solidarity, which she termed as unsustainable solutions in the face of recurring disasters.

Al-Qadri called for the establishment of civil associations and community-based emergency teams trained specifically in early warning, to be distributed across high-risk areas and operating in coordination with official entities. She also stressed the importance of involving media and schools in awareness efforts: “Disaster response culture must become part of school curriculum and public media discourse.”

In addition, the environmental expert highlighted the importance of adopting advanced technologies such as remote sensing, satellite image analysis, and the development of highly accurate future prediction models, especially in light of growing climate change that complicates forecasting and early warning efforts.

Proposed Solutions and Practical Interventions

Official entities and experts in the meteorological sector do not hide the harsh realities under which Yemen’s early warning centers operate—marked by massive funding gaps, lack of equipment, and staff attrition. These challenges weaken the effectiveness of any alerts issued and reduces their field impact. The obstacles facing this vital sector are no different from those afflicting all state institutions in general, but they are far more sensitive due to their direct impact on people’s lives and property.

In Hadramout Governorate, Engineer Abdulrahman Hameed stated that the center faces multiple challenges, foremost being “insufficient operational funding to sustain activities, lack of modern technical equipment, and a shortage of qualified and trained personnel.” He added that the reluctance of specialized professionals to join the center is directly linked to low salaries and the absence of a motivating work environment, amid the overall deteriorating living conditions.

Hameed noted that several requests submitted by the center for upgrading the equipment, training of staff, and securing regular financial support, have so far received only promises that remain to be fulfilled.

In Aden, Engineer Ali Batisir warned of a sharp decline in the readiness of meteorological centers, stressing that upgrading the weather monitoring network is now an urgent necessity. He explained that priorities include installing modern automatic monitoring stations, providing weather radars, and acquiring high-resolution satellite imagery, particularly in coastal and mountainous areas prone to cyclones, landslides, and flash floods.

Batisir emphasized that developing the capacities of national personnel is a decisive element in any future plan, calling for the training of local specialists in advanced numerical forecasting models and the development of accurate local models capable of interpreting Yemen’s complex weather patterns.

He also called for “increased financial and technical support for the meteorological sector, and improved coordination mechanisms with government agencies and relevant organizations, especially civil defense, agriculture, water, and relief sectors”.

Batisir added that enhancing community awareness is a core part of the strategy, particularly in rural areas lacking basic services. He pointed out that disaster response does not begin when the crisis hits—it starts with prior awareness.

From Sanaa, Engineer Mohammed Al-Lisani stated that the key challenges facing the meteorological sector go beyond equipment shortages. They also include the “inability to sustain training and capacity-building, lack of new qualified personnel, and institutional instability caused by the ongoing conflict.”

Al-Lisani explained that the National Meteorological Center continues to operate 24/7, monitoring and analyzing weather maps and converting data into useful public information, despite all obstacles. However, he stressed that the continuation of this work depends on the availability of equipment and resources, expansion of the monitoring network, and ongoing training of personnel both locally and abroad.

Dr. Nabila Al-Qadri confirmed that the current situation has negatively impacted the efficiency of climate monitoring stations in Yemen, noting that many have ceased operations—especially those tasked with flood monitoring. She added that some key stations suffer from data interruptions and operational difficulties due to lack of funding and maintenance.

Al-Qadri proposed starting with the rehabilitation of inactive monitoring stations and establishing new ones in high-risk areas, alongside forming community emergency teams, activating the media and schools in spreading the culture of disaster response, and adopting modern technologies such as remote sensing.

Despite the recurrence of climate disasters in Yemen, official evacuation plans still lack inclusivity and transparency. There are no binding legal guarantees that account for the specific needs of the most vulnerable groups. Between funding shortages, deteriorating infrastructure, and the absence of a national strategy, Yemeni lives remain at the mercy of nature—while disasters continue to claim more victims, often without a single warning siren to save those who could have been saved.