Photo Designed by South24 Center

31-07-2025 at 11 AM Aden Time

|

|

"The recent Gaza war represented a further turning point in the Houthis' path toward Houthi-ization of education, as the group treated the event as a golden opportunity to reinforce its ideological discourse".

*Ibrahim Ali (South24)

Since the Houthi group took control of the capital Sanaa and several Yemeni governorates in 2014, education—particularly changing school curricula—has emerged as one of the most prominent tools through which the group has sought to entrench its ideology and expand its doctrinal influence over society. However, the group’s awareness of this issue’s sensitivity initially prompted it to approach the matter with great caution, despite early recognition of its importance as a means to reshape the consciousness of future generations.

For a religious group with sectarian leanings, it was no easy task to impose its vision on a diverse society whose religious and social values largely do not align with the group’s closed and historically different narrative. Even when the group imposed a blockade on Sanaa in preparation for its takeover, it wrapped its project in moral and populist justifications, initially raising slogans opposing the economic decisions of Mohamed Salem Basindwa’s government1 —particularly regarding the "price hike” in an attempt to portray itself as a savior from the daily suffering of citizens.

However, education—and curricula in particular —proved a more complex issue. Changing the content of school textbooks does not go unnoticed in society, especially in a country that has previously experienced harsh ideological shifts over past decades. Therefore, the Houthis approached this issue in phases, gradually introducing changes often cloaked under general national and religious banners. The alterations did not begin with sweeping cancellations or direct replacements but rather with scattered amendments that appeared innocuous on the surface yet carried political and doctrinal messages that served the group’s long-term project goals.

Phase One: Covert Preparation (2014–2017)

In 2015, with the onset of the Saudi-led Arab coalition’s military intervention against the Houthis, the group found strong justification to proceed with its educational project. The war became an ideal propaganda platform, enabling the group to present itself as “the sole force resisting external aggression”, and to promote the idea that previous curricula were “infiltrated” by ideologies that, according to its claims, threatened Yemeni identity. This propaganda framework paved the way for presenting curriculum changes as a “counter-ideological war,” rather than mere educational reforms.

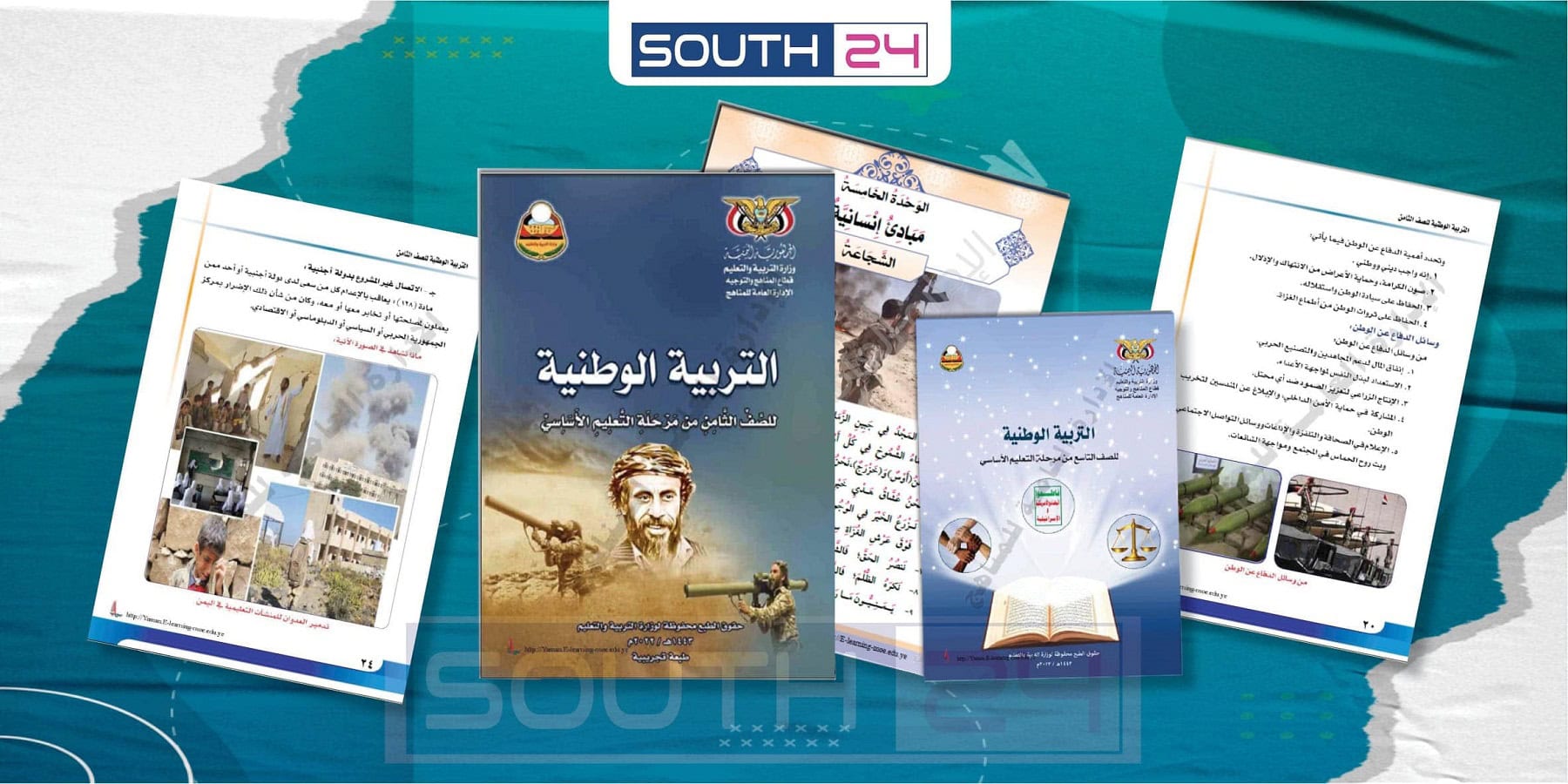

The Houthis used this pretext to reshape textbooks—particularly history, Islamic education, and national education—by removing concepts related to the modern state and limiting pluralism in favor of promoting the group’s symbols and slogans. They also inserted religious and political narratives portraying the group as a continuation of the “true Imamate”, and depicted the ongoing war as a “holy jihad” against foreign aggression.

These changes appear to be part of a broader ideological project aimed at creating a generation steeped in the group’s ideology and loyal to it politically and religiously. However, the ongoing conflict and the Houthis’ failure to fully control northern Yemen—or gain any foothold in the South—have hampered the full imposition of these curricula nationwide.

While the group continues to promote these changes as “national reform”, observers view the process as an attempt to mold the collective consciousness of Yemeni children according to a narrow sectarian vision, one that could have profound and troubling effects over time, complicating any future national reconciliation efforts.

Phase Two: Empowerment and Domination (2018–2022)

In the period following the 2014 coup, the Houthi group faced multiple challenges in its efforts to implement radical changes to the educational curricula, most notably the presence of the General People's Congress (GPC) as a partner in governance, led by former President Ali Abdullah Saleh. This relative political balance, coupled with societal sensitivity toward tampering with education, compelled the group to proceed cautiously, fearing backlash that could derail its project to “Houthify” education.

In this context, the GPC—then still allied with the Houthis—firmly rejected any curriculum changes without broad national consensus. The party’s weekly newspaper ‘Al-Mithaq’ quoted a source in the party’s educational division expressing total opposition to any amendments without the agreement of all political forces. The source warned that unilateral actions by the Ministry of Education could have dangerous consequences, potentially prompting the GPC to adopt a final and firm stance on its participation in the Houthi government. The party also strongly criticized the fact that such amendments were being made “in secret”, without consulting even the curriculum committee, whose work had been suspended, calling the move a breach of established consensus-based practices.

However, this alliance of necessity did not last long. In December 2017, tensions exploded into violent conflict, ending with Saleh’s assassination and the Houthis taking complete control over areas under their rule. This pivotal moment granted the group greater freedom of movement, unhindered by internal political oversight. This was quickly translated into practical steps to reengineer the curricula in line with its ideological doctrine.

In the years that followed, the pace of curriculum amendments accelerated, introducing sectarian and historical content reflecting the group’s narrative of the conflict, and reinforcing concepts of absolute loyalty to its leadership. National symbols were removed from textbooks and replaced with religious figures associated with the Zaydi sect (thought) as role models for students.

By the 2021/2022 academic year, the Ministry of Education in Sanaa unveiled new and revised textbooks covering Islamic education, Quranic studies, and social sciences for primary school students. Lessons reinforcing the group’s doctrinal narrative were introduced, while content concerning civil rights, women’s roles, and the history of influential national figures were either deleted or modified. These changes stirred considerable debate about whether they were aimed at reshaping the consciousness of future generations to serve the group’s political and ideological project.

The changes were not limited to primary schools but extended to technical, vocational, and community colleges, where the group imposed strict oversight on lecture content and professors’ views. While these interventions were justified as efforts to “protect national identity”, they reflect a systematic approach to creating an indoctrinated generation with a singular worldview—raising serious concerns about the long-term consequences on Yemen’s cultural and social fabric.

• The changes included the curricula of Arabic language, Islamic education, civic education, and history at the primary school level.

• National figures such as Mohammed Mahmoud Al-Zubayri and Ali Abdul-Mughni were replaced with Zaydi Imamate figures like Al-Qasim, Al-Mansour, and Yahya Hamid Al-Din.

• The Houthi takeover of Sana'a in 2014 was glorified as a “revolution”, while the Arab coalition was vilified as the “American-Zionist coalition”.

• All references to the September 26, 1962 revolution and the founding of the republic were removed, especially from the eighth -grade curriculum.

• Lessons on the state, executive authority, authoritarian rule, and civil society were eliminated and replaced with content on “national identity” according to the group’s vision.

• In the ninth grade, lessons on women’s participation and civic life were removed.

• Students were compelled to participate in religious activities and Houthi-sponsored events that glorify the group and attack the internationally recognized government.

Phase Three: The Gaza War - A Strategic Leap (2023–2024)

The recent Gaza war marked a further turning point in the Houthis’ trajectory toward ‘Houthification’ of education, as the group treated the conflict as a golden opportunity to reinforce its ideological discourse and justify further amendments to curricula.

Although the war erupted in the middle of the academic year, the group quickly introduced a new subject titled “Educational Guidance” during the final weeks of school. This subject was officially incorporated into the curricula in Houthi-controlled areas, capitalizing on the heightened emotions surrounding the Palestinian cause to push through its content.

Contrary to expectations of the material being centered on empathy for the Palestine cause, it is steeped in sectarian and ideological themes linked to the group’s religious identity and project. It is designed to be taught weekly from the fourth grade through the end of high school, and is based on the writings of the group’s founder Hussein al-Houthi and speeches by its current leader Abdul-Malik al-Houthi. The lessons are delivered under the direct supervision of Houthi-aligned religious activists, making them more akin to ideological mobilization sessions than conventional educational content.

Although the subject’s apparent title is “Supporting Palestine”, its practical content emphasizes on glorification of the Houthi leadership and religious sanctification of both the group’s founder and current leader—portraying them as part of the “Axis of Resistance” and “Guardians of the Nation”. This dangerous fusion of major national causes with narrow sectarian agendas transcends mere media or festival rhetoric and has now infiltrated classrooms in the form of structured lessons.

If the group ensured that last year did not pass without amendments, it is highly likely that the current academic year will witness more substantial changes, especially amid a surge in the group’s mobilization narrative and its attempt to draw permanent links between its leadership and regional conflicts, primarily the conflict with Israel, especially in light of its growing role in the war.

This educational trajectory has sparked widespread concern among educators, who fear that schooling may shift from a means of building civic and national consciousness to a tool for creating an ideologically indoctrinated generation—one that views allegiance to a religious leader as the sole criterion for identity and belonging, and war as a means of self-expression.

Final Recommendations

1. Community Awareness: It is necessary to strengthen awareness among Yemeni families regarding the dangers of the modified curricula, support local initiatives to monitor such ideological changes, and promote balanced alternative knowledge through media and community platforms.

2. Domestic and International Pressure: Urge the international community and the United Nations to pressure the Houthi group to halt sectarian changes to curricula, and to link any financial or political support to guarantees of educational neutrality.

3. Activate the role of Human Rights Organizations: Encourage both local and global rights groups to document the group's violations in the education sector and highlight them in international forums.

4. Support Schools in Government-Controlled Areas: Provide backing to schools and educational centers in areas under the control of the Yemeni government, to preserve curricula free from sectarian agendas.

5. Engage Educational Elites: Encourage Yemeni educators and intellectuals to produce alternative educational content that is apolitical and counters the sectarian indoctrination efforts.

6. Establish Independent National Committees: Create independent national committees to oversee curriculum development in the post-conflict stage, ensuring alignment with the principles of justice and peace.

7. Protect Education from Political Exploitation: Advocate for the separation of education from ideological conflicts and uphold it as a fundamental right for children, free from political manipulation.

Previous article