Designed by South24 Center

Last updated on: 11-07-2025 at 7 AM Aden Time

|

|

By Mokhtar Sha’tal | South24 Center

Edited by Jacob Al-Sufyani

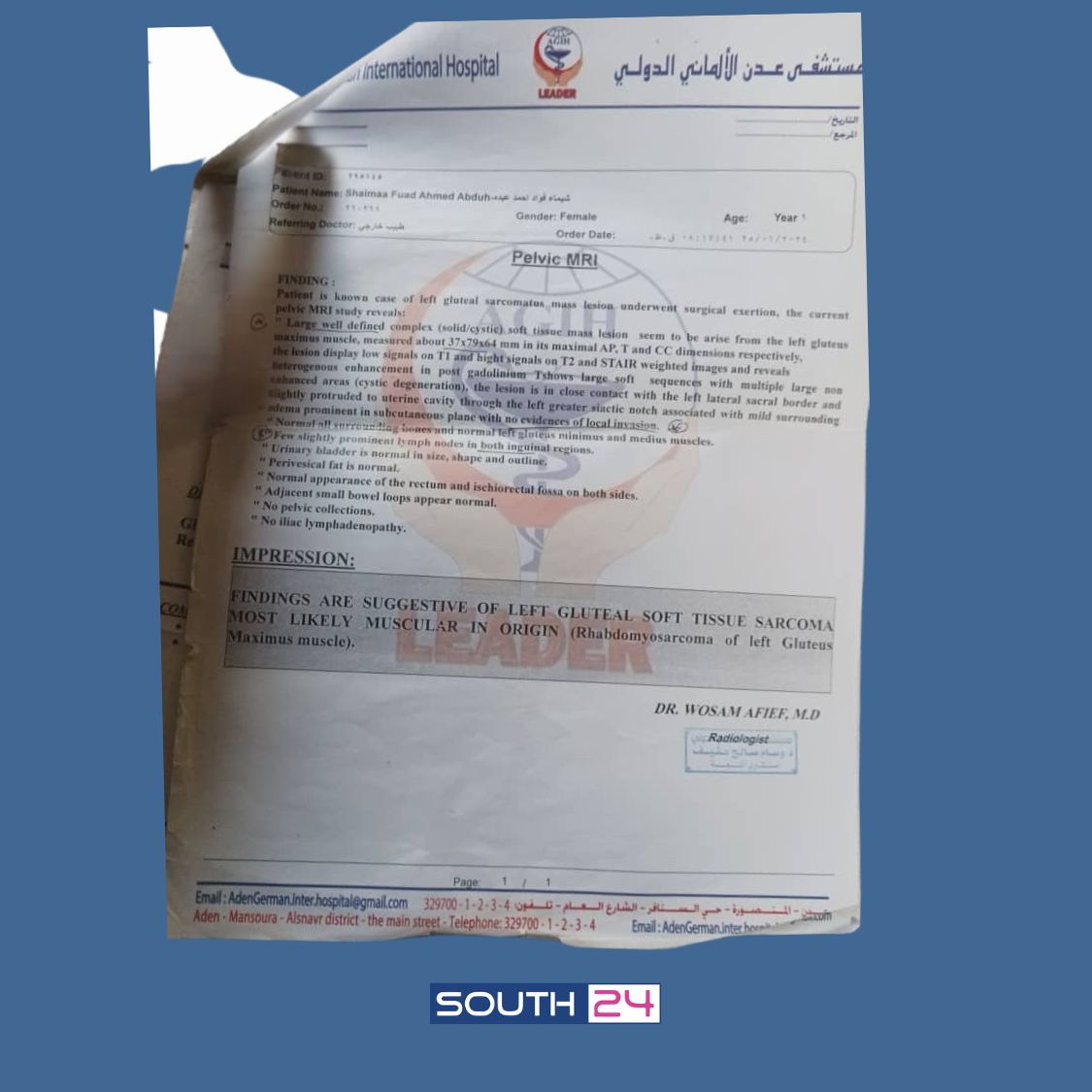

Lahij, Yemen — Four-year-old Shaima Fuad Ahmed lies in a hospital bed in Aden, her spine ravaged by a malignant tumor. Her father blames the coal emissions from the nearby National Cement Company factory in Lahij for the disease that has required Shaima to undergo multiple surgeries and ongoing chemotherapy treatment.

Located in the Sa’am Valley, between the Al-Musaymir and Al-Malah districts, the factory is operated by Yemen’s largest conglomerate, the Hayel Saeed Anam Group. According to medical records reviewed by ’South24 Center‘, Shaima’s case is one of many blamed by residents to toxic emissions from the plant’s coal-fired power station.

Shaima Fouad Ahmed's cancer diagnosis report from Aden-German International Hospital

A growing body of evidence suggests that the plant, which began operations between 2006 and 2008, has contributed to a public health crisis. A 2021 community-led report documented 159 cases of illness or death in Al-Musaymir alone—52 of them fatalities. The reported illnesses include asthma, cancers, kidney and liver failure, heart disease, and birth defects. Investigators have attributed the surge to pollution from the coal plant.

Location of the National Cement Factory in Lahj Governorate (Google Earth - via South24 Center)

“This isn't an isolated incident,” said Mohsen Mohammed Al-Rabeeh, a retired teacher and community leader who led the local investigation. “The emissions are affecting entire families.”

The impact has extended to the neighboring Al-Malah district, where local medical staff report a high daily caseload of respiratory illnesses. Dr. Basem Musleh Mohammed, a medical assistant at Al-Malah’s primary health unit, told ’South24 Center‘ that up to 50 patients arrive each day, with as many as 15 suffering from asthma.

Between 2010 and 2018, official health data [1] from Al-Malah recorded more than 29,000 respiratory cases and 37 cancer-related deaths. Local authorities say that cases of lung, stomach, and liver diseases have surged over the past decade.

Academic research supports these claims. A 2021 peer-reviewed study by University of Aden researcher Antar Al-Sha’ibi found a direct correlation between operations at the National Cement Company factory and widespread illnesses in Al-Musaymir and Al-Malah. Children were identified as the most affected group, accounting for 33% of cases studied, followed by women and the elderly.

Environmental degradation has accompanied the public health crisis. Agricultural output in Al-Musaymir has reportedly declined by 60% since the factory and its coal plant became operational, according to Abdul-Habib Mahmoud Saleh, head of the district’s Agriculture and Irrigation Office.

“Crop production has collapsed,” Saleh said. “Ash, dust, and toxic gases from the coal station have devastated local farming.”

Residents also cite acid rain as a recurring phenomenon that has damaged crops and wiped out bee colonies. Local livestock has not been spared either. Saleh’s office recently recorded the death or illness of up to 2,000 sheep due to what he described as “climate effects and smoke emissions.”

In the village of Al-Zafeer, Abdullah Ali Salem Al-Daws, a local council member, described the economic fallout: “We’ve lost our livelihoods. Our land is no longer arable.”

Another resident, Abdullah Mohsen Ali Saeed from Al-Malah, said pollution has decimated his beekeeping business and livestock. “I had 90 beehives; only 40 remain, and they no longer produce,” he said. “I also lost 30 out of 40 sheep.”

Despite mounting health and environmental concerns, there has been no formal regulatory action on the factory’s operations. Residents say they have received no support or intervention from government authorities, leaving communities to bear the burden alone.

As Shaima continues her chemotherapy treatment, her father reflects on the price his family has paid. “We thought surgery would be the end of it,” he said. “But the tumor came back. And the factory continues to operate, unchecked.”

Environmental Contamination

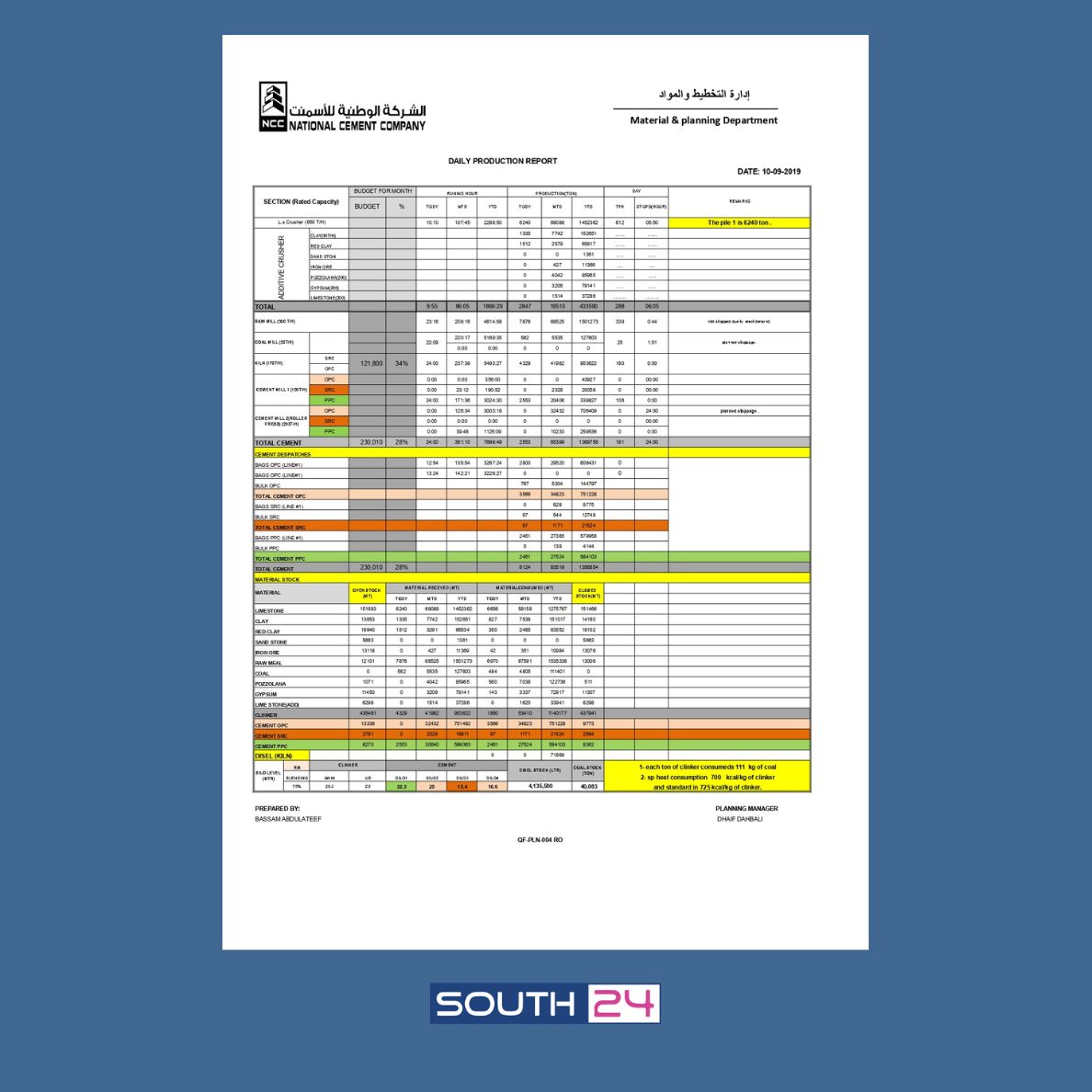

Scientific findings collected around the National Cement Company factory in Lahij reveal substantial environmental degradation tied to the plant’s coal-powered operations. Laboratory analysis of emissions and soil samples indicate that the facility, which consumes an average of 111 kilograms of coal [2] per ton of clinker produced, is operating near the upper threshold of thermal industry standards.

A report from the National Cement Factory on coal consumption for electricity generation.

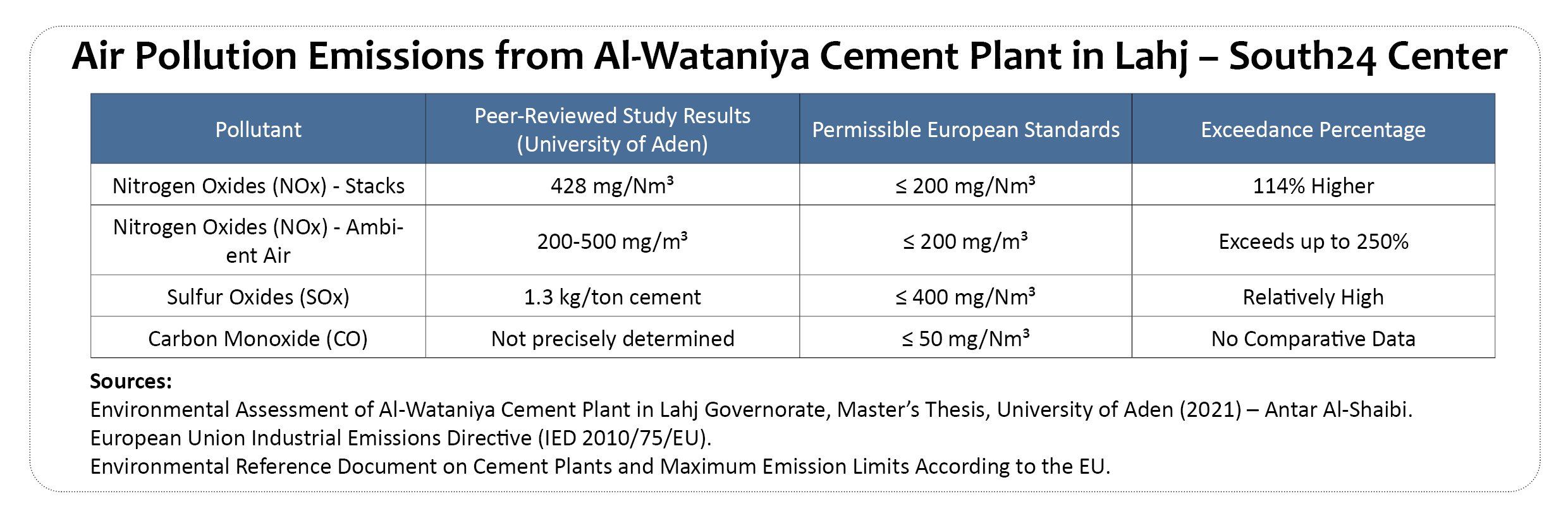

Research led by University of Aden environmental specialist Antar Al-Sha’ibi confirms that combustion byproducts from the plant’s furnaces—particularly carbon dioxide (CO₂), sulfur dioxide (SO₂), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and carbon monoxide (CO)—are released in significant volumes [3]. Atmospheric CO₂ concentrations in the factory’s vicinity were found to exceed natural baseline levels, a direct result of the plant’s dependency on coal combustion.

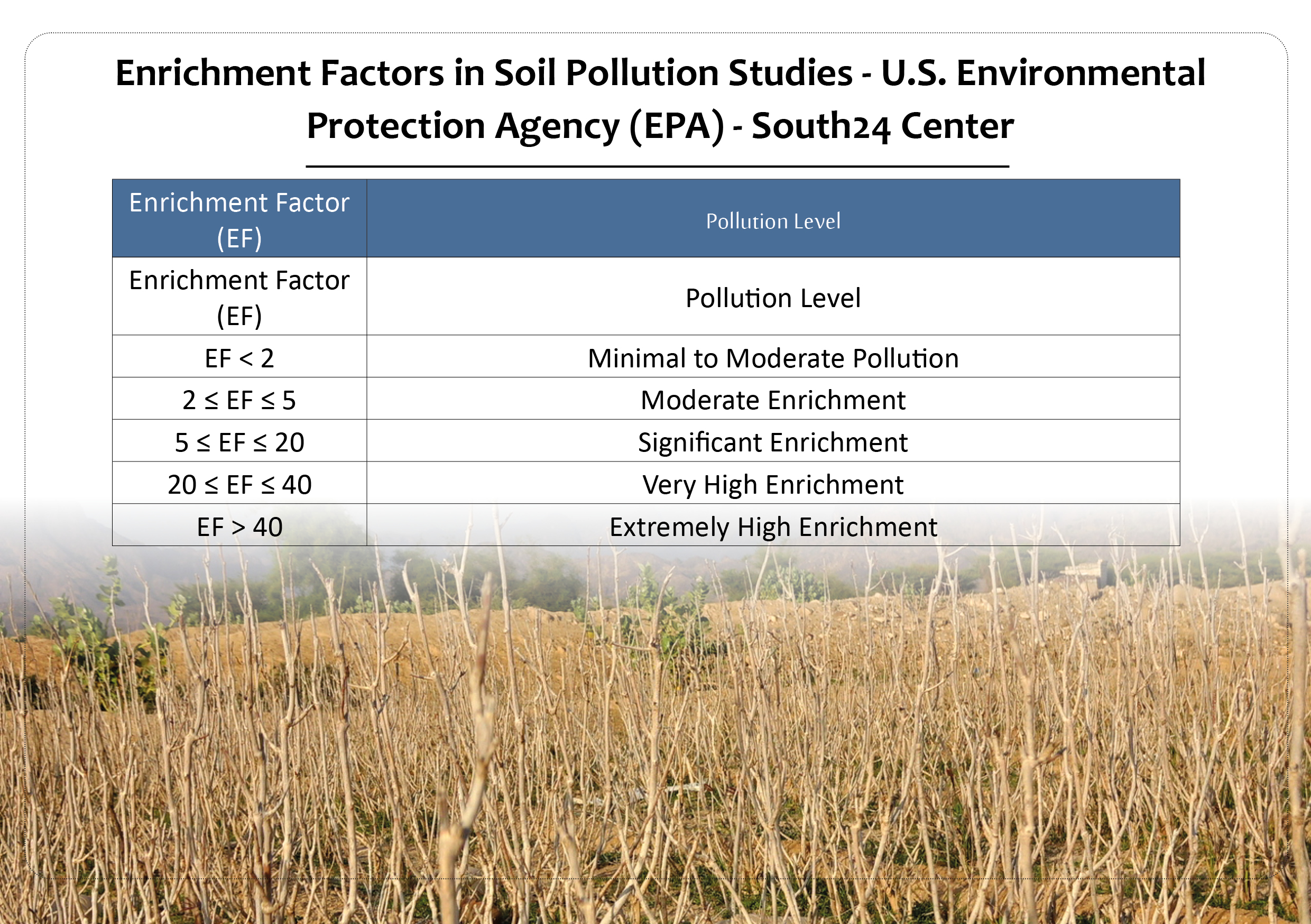

Soil testing conducted as part of the same study included 11 samples—three from within the plant perimeter and eight from its surroundings at distances of 500 and 1,000 meters in four directions. The results revealed moderate contamination levels for lead, copper, and nickel, while cadmium and zinc levels indicated “severe enrichment”, reaching thresholds categorized by the US Environmental Protection Agency as extreme [4].

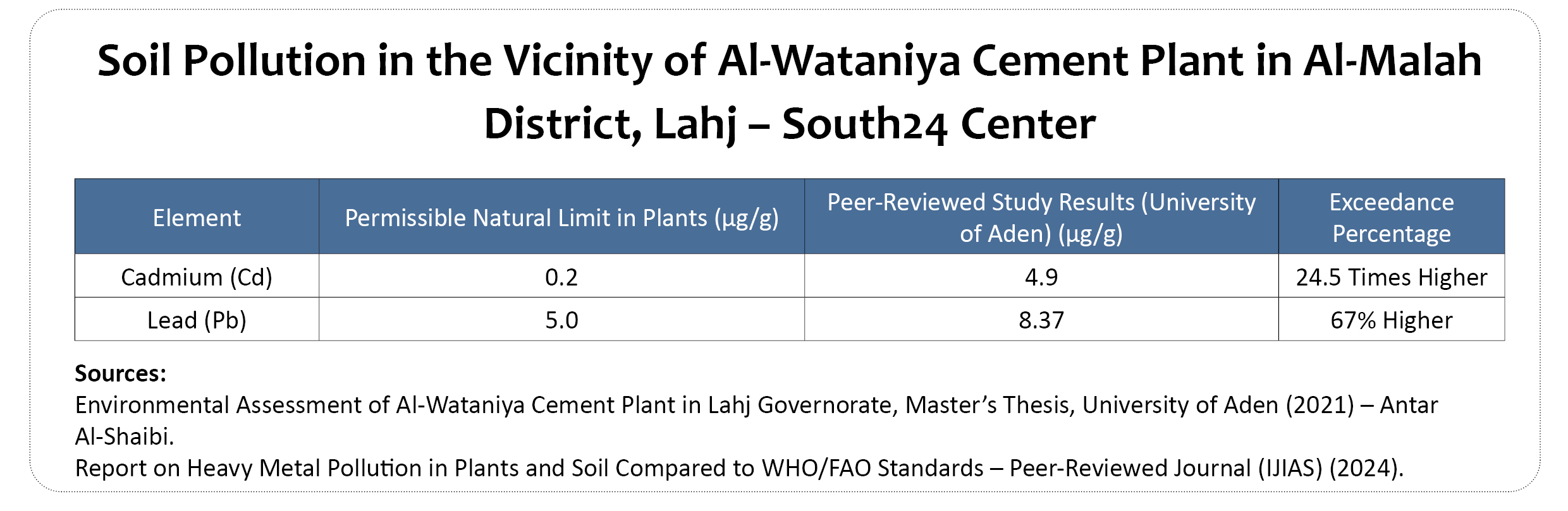

Plant tissue samples collected near the factory also contained heavy metal concentrations far above internationally accepted limits. The average cadmium concentration reached 4.9 micrograms per gram—more than 24 times the global safety limit, while lead averaged 8.37 micrograms per gram, surpassing the recommended threshold by 67%. These readings suggest significant bioaccumulation of toxic elements in local flora, increasing the risk of transmission through the food chain [5].

Air quality measurements point to poor combustion efficiency [6]. CO emissions were elevated, and SO₂ output stood at 1.3 kilograms per ton of cement. NOx emissions measured 3 kilograms per ton, while ambient concentrations in surrounding areas ranged from 200 to 500 milligrams per cubic meter—exceeding EU regulatory limits by up to 250%.

Stack emission readings recorded 428 mg/Nm³ (milligrams per normal cubic meter) of NOx from the kiln and raw material mills, and 88 mg/Nm³ from the coal mill. These values place the factory at the upper end of the European benchmark range for plants without emission reduction technologies (200–500 mg/Nm³), further reinforcing its status as a high-impact pollution source.

Despite these findings, the factory lacks any advanced filtration or gas treatment systems. It operates without monitoring equipment for the sulfur dioxide or carbon monoxide produced, meaning that pollutant levels are neither tracked nor controlled. Global standards cap SO₂ emissions at 400 mg/Nm³ and CO at 100 mg/Nm³, but without real-time monitoring, the factory’s compliance remains unverifiable.

Smoke emitted from the National Cement Factory in Lahj Governorate (study by researcher Antar Al-Shaibi at the University of Aden)

The plant is also not equipped with wastewater treatment infrastructure, raising the likelihood that its chemical pollutants and heavy metals are seeping into nearby groundwater supplies. Environmental researchers warn that this poses a direct threat to local agriculture, ecosystems, and public health.

Prof. Mohammed Muttash Al-Yafaei, a geothermal energy expert and senior geologist, corroborated these concerns. “Coal combustion generates airborne particulates that contribute to smog and acid rain,” he said in an interview. “The fly ash travels with the wind, contaminating soil, crops, wells, and open water sources across Al-Malah and Al-Musaymir.”

Al-Yafaei added that coal-based emissions typically contain volatile particles of mercury, arsenic, and cadmium—highly toxic elements capable of traveling through the atmosphere and settling in agricultural valleys and water systems. He further pointed to the plant’s role in accelerating climate change, citing CO₂ emissions as a major factor in global warming and ozone depletion.

Legal Framework

Yemen’s legal code provides a broad framework intended to regulate industrial pollution and protect public health, but implementation gaps and weak enforcement have left communities vulnerable to environmental harm.

Environmental Protection Law No. 26 of 1995 [7] outlines the state’s responsibility to safeguard the public and preserve biodiversity from industrial and ecological threats. The legislation affirms every citizen’s right to live in a healthy and balanced environment that supports physical, mental, and developmental well-being. It also imposes legal obligations on both government agencies and private entities to prevent pollution and conserve natural resources.

One of the law’s key provisions, Article 3, Clause 9, holds polluters financially accountable, stating that “anyone who causes environmental harm shall bear the full cost of damage removal and compensate affected parties.” The law assigns joint responsibility to both public authorities and private operators to prevent and address environmental degradation.

In practice, however, these protections remain largely theoretical. Oversight is limited, regulatory follow-through is inconsistent, and affected populations often lack access to legal recourse or compensation mechanisms.

Internationally, Yemen is party to several agreements that reinforce domestic environmental commitments. The 1972 Stockholm Declaration and the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change establish the legal principle of “no harm”, which obligates countries and companies to ensure that industrial activities do not cause environmental damage—either within national borders or across them [8][9]. This principle forms the basis for restricting pollution that could endanger ecosystems or human populations.

Equally important is the “polluter pays” principle, which compels companies responsible for environmental damage to bear the financial and legal consequences. The standard has been cited in numerous international court cases requiring corporations to fund cleanup efforts and provide restitution for affected communities.

Additional provisions emphasize public transparency and community participation. Under widely accepted international norms, governments and companies are expected to disclose emissions data, report pollution levels, and engage civil society in environmental monitoring. These measures are designed to enhance accountability and enable early intervention in environmental crises.

Finally, the principle of environmental liability calls for enforcement mechanisms, including fines, legal sanctions, and regulatory oversight to prevent repeat violations. This is particularly critical in countries with limited institutional capacity, where legal loopholes and administrative weaknesses often allow industrial actors to operate with impunity.

Despite these legal safeguards, the situation surrounding the National Cement Company factory highlights a gap between legal intent and practical enforcement—leaving affected residents to bear the brunt of unchecked industrial activity with little recourse to justice or remediation.

Community Resistance

Amid rising health concerns and environmental degradation, residents of Al-Musaymir and Al-Malah districts have turned to protest and formal complaints in a bid to curb emissions from the National Cement Company. Despite years of appeals, residents say their efforts have yielded few results, and frustration with official inaction continues to mount.

Local communities have submitted written petitions to the Governor of Lahij and the Environmental Protection Authority, filed complaints with municipal authorities, and staged demonstrations outside the factory, demanding an end to coal combustion at the site and enforcement of environmental standards.

In 2021, following sustained public pressure, local authorities formed a committee led by Faisal Saleh Al-Tha’labi, acting head of the General Authority for Environmental Protection. The committee was tasked with assessing the environmental and health impacts linked to the plant. But the outcome failed to meet public expectations.

A confidential document obtained by ‘South24 Center’ from the Lahij office of the Ministry of Human Rights confirmed the presence of “significant health and environmental consequences” stemming from coal usage at the plant. According to Hayat Al-Ruhaibi, the office’s director, the assessment committee included four technical experts and four community representatives. Fieldwork began on November 28, 2021—five days after the committee was formally established.

Despite this, the committee provided no conclusive explanation for the spike in illness among nearby residents, prompting renewed demands from the community to halt the use of coal altogether.

For over two months, the ‘South24 Center’ investigative team sought interviews with regulatory authorities and the factory management to present the collected data and seek an official comment. Most requests were either ignored or deferred. Fathi Al-Sa’ou, head of the Environmental Protection Office in Lahij, referred the inquiries to a subordinate, Ismail Al-Hilli, who did not respond prior to publication.

Engineer Faisal Al-Tha’labi, who chaired the official committee, offered only a brief comment to ‘South24 Center’ when reached by phone: “How else would the factory operate in the face of power outages and rising fuel costs?”—a response that residents say reflects a lack of concern for the human cost of industrial pollution.

The factory’s management also declined to engage. Director Salem Badr initially agreed to an interview with ‘South24 Center’ but failed to follow up despite repeated requests over the course of a month, raising further questions about transparency and accountability.

According to Ahmed Al-Sayyed, director of the local health office, and Abdul-Habib Mahmoud Saleh, director of the agriculture office in Al-Musaymir, reports compiled by local government committees have yet to be submitted to the relevant departments. Both officials acknowledged that final findings remain unknown to their offices.

Residents, meanwhile, allege that these committees have acted in collusion with the factory management, prioritizing private interests over public health. “There’s no transparency,” said one resident. “The people living near the factory are paying the price with their lives.”

With government oversight limited and corporate accountability absent, local families continue to face escalating health risks and environmental loss—awaiting meaningful intervention that has yet to arrive.