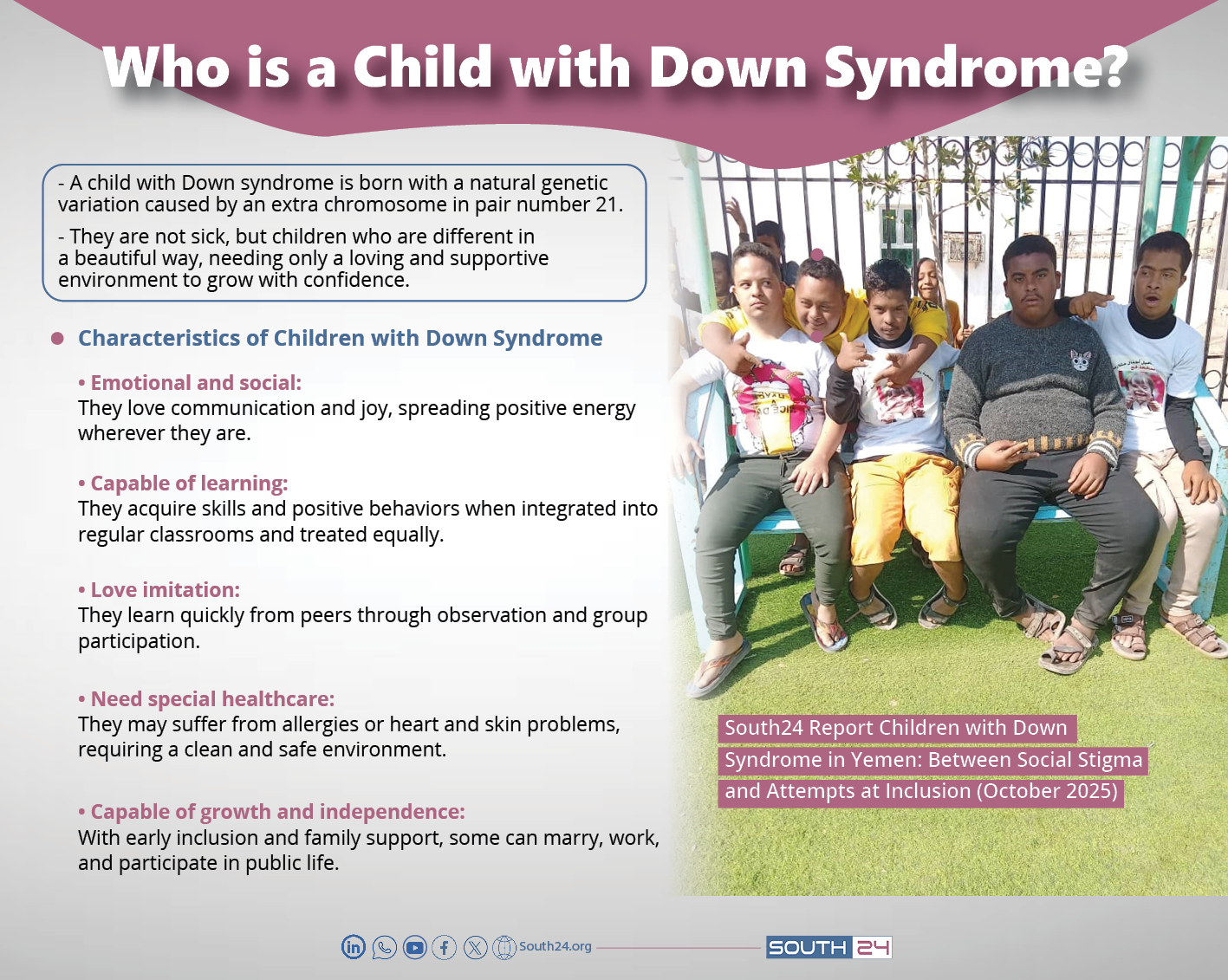

Children with Down syndrome at the ‘Sunrise’ Center for Autism and Intellectual Disabilities in Sanaa, October 5, 2025 (South24 Center)

30-10-2025 at 1 PM Aden Time

|

|

“Parents’ open acceptance of their child and support in front of others is the first step to breaking the barriers of social stigma, because emotional support at home directly reflects in the child’s development.”

Fatma Al-Ansi & Sarah Nwaijaa (South24 Center)

In a country torn by war and where hope has narrowed to a thin margin, children with Down syndrome fight a dual battle: one against a deeply rooted social stigma, and another against institutional absence that leaves them without education, care, or legal protection.

Although Down syndrome is not a disease but a simple genetic variation, in Yemen it turns into a harsh social judgement that pushes these children to the margins of life.

Yet, against this reality, modest initiatives and small centers emerge, striving to restore these children’s right to inclusion, joy, and life.

The following South24 report traces their journey between stigma and acceptance, unpacks the roots of marginalization in a society exhausted by crises, and shows how love and awareness can be remedies stronger than any medicine.

Social Stigma

In Yemen, children with Down syndrome face not only physical or cognitive limitations, but also collide with a wall of social stigma that begins within the home and extends to the community. Shame surrounding their being “different” remains present in the culture of many families, with some even choosing to hide their children from public view in fear of inviting people’s reactions or their gossip, as if having Down syndrome were a disgrace that needs to be concealed.

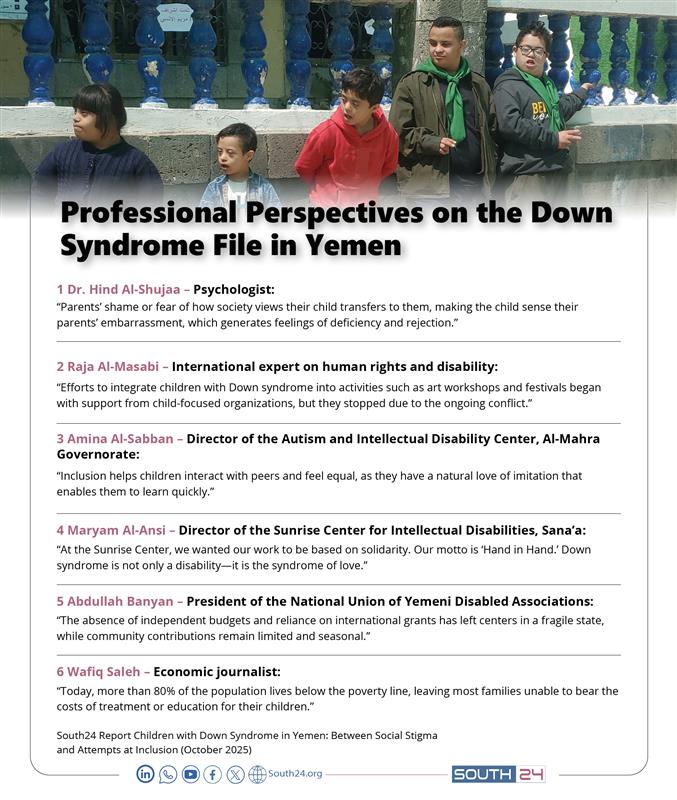

Psychologist Hind Al-Shujaa affirms that witnessing adverse reactions in their parents leaves deep scars on the child’s psyche. She told South24: “The parents’ feelings of shame or fear of how society perceives their child transfers to them. The child senses their parents’ embarrassment, which produces a feeling of deficiency and rejection and increases the likelihood of developing anxiety and isolation later.”

This early awareness—as Al-Shujaa explains—disrupts emotional communication between parents and the child, and the child grows up in a cautious, hesitant environment that restricts interaction with others and weakens their self-confidence.

She points out that isolating the child from society in the early years often leads to delays in language and social development, and an excessive fear of new experiences and situations, because the child has not learned to engage with others beyond the narrow circle of the family.

Al-Shujaa emphasizes that parents’ public acceptance and support of their child is the first step to breaking the barriers of social stigma, as emotional support at home directly reflects in the child’s development and psychological balance. In contrast, hiding the child or feeling ashamed of them creates a dual form of isolation: psychological isolation within the family, and social isolation outside it.

Integration Efforts

Despite the difficult social reality, the Yemeni scene has not been devoid of inspiring flashes of hope – of families seeking to integrate their children with Down syndrome into public space. However, these initiatives are often short-lived—rising out of humanitarian enthusiasm and then collapsing under the storms of war and shrinking funding.

Raja Al-Masabi, an international expert on human rights and persons with disabilities, told South24: “Efforts to integrate children with Down syndrome into child-focused activities—such as drawing workshops, festivals, and educational sessions—began recently through a number of children’s welfare organizations like UNICEF and humanitarian associations, but they stopped due to the ongoing conflict.”

This halt, as Al-Masabi explains, was not merely a suspension of activity, but a suspension of hope. The war that destroyed infrastructure also took down the humanitarian spaces where these initiatives were born, and shut many associations and centers that had embraced children and provided them with safe environments for learning and interaction.

Education remains the most sensitive domain in the trajectory of integrating children with Down syndrome, as it serves as a gateway to personality building, capacity development, and self-discovery. Yet this door in Yemen often opens only slightly, not allowing all children to pass through.

Amna Al-Sabban, director of the Autism and Intellectual Disability Center in Al-Mahra Governorate, believes that integrating children with Down syndrome into regular classrooms is key to building confidence and stimulating their abilities.

She added to South24: “Inclusion helps children interact with their peers and feel a sense of equality, which dispels the sense of difference and encourages social and educational participation. Children with Down syndrome have a unique trait—the love of imitation—which enables them to quickly acquire positive skills and behaviors from their classmates.”

But this inclusion is not without difficulties, Al-Sabban adds, as some children face bullying or isolation within the school environment, in addition to academic challenges stemming from relative cognitive limitations.

Al-Sabban sees the crux of the problem in the nature of the educational curricula, as the current syllabi does not take into account the needs of this group. She explains that the curricula for children with Down syndrome should be based on active learning and the use of visual and practical tools instead of traditional rote learning, because experience and practice are far more effective than abstract memorization.

She points out that Yemeni society has witnessed in recent years a gradual positive transformation in its view of children with Down syndrome, with increased awareness and acceptance, and the establishment of specialized centers to enable them to access education and rehabilitation. As a result, some of them later in life —as she confirms—have been able to marry and start families, which clearly indicates that inclusion can yield tangible results when both the will and a supportive environment are present.

Inspiring Stories

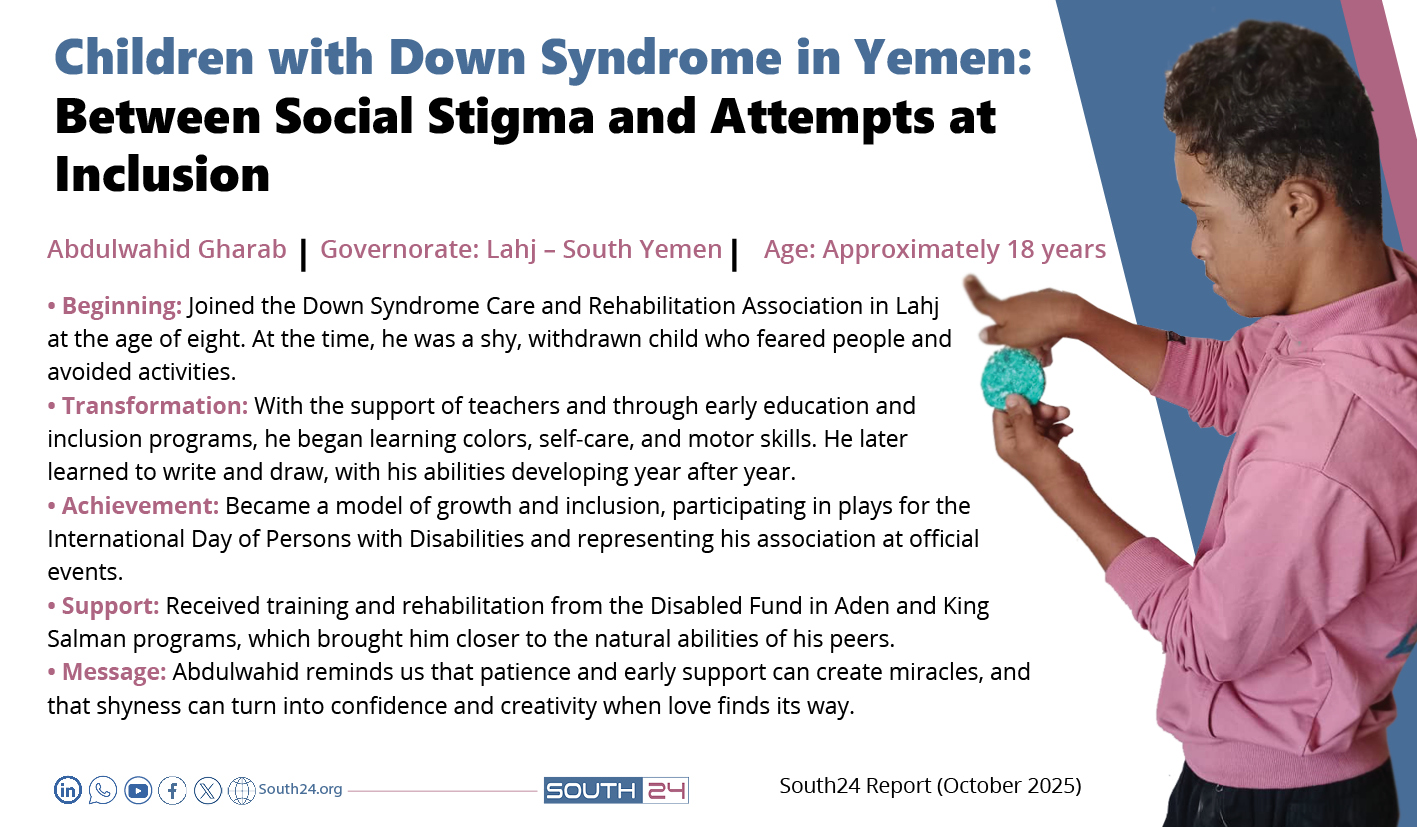

Abdulwahid: From An Introvert to the Stage

When Abdulwahid Ghorab joined the Down Syndrome Care and Rehabilitation Association in Lahj Governorate, he was eight years old—a shy, withdrawn child who feared people and did not participate in any activity. But that simple beginning gradually turned into an astonishing transformation, thanks to teacher support and early education and inclusion programs.

Majida Al-Nafeeli, the head of the association, told South24: “Teachers started by teaching him the basics of color recognition, self-care, and motor skills. His inner curiosity prompted him to learn, and over time he began to write and draw. Then his abilities developed year after year.”

Today, after a full decade of perseverance, Abdulwahid has become a model of development and inclusion. He participates in plays marking the International Day of Persons with Disabilities and represents his association at official national events.

Abdulwahid’s experience was not limited to education; it was also a journey of self-rediscovery. The support he received from the Disabled Fund in Aden and from the King Salman program brought him close to the natural abilities of his peers.

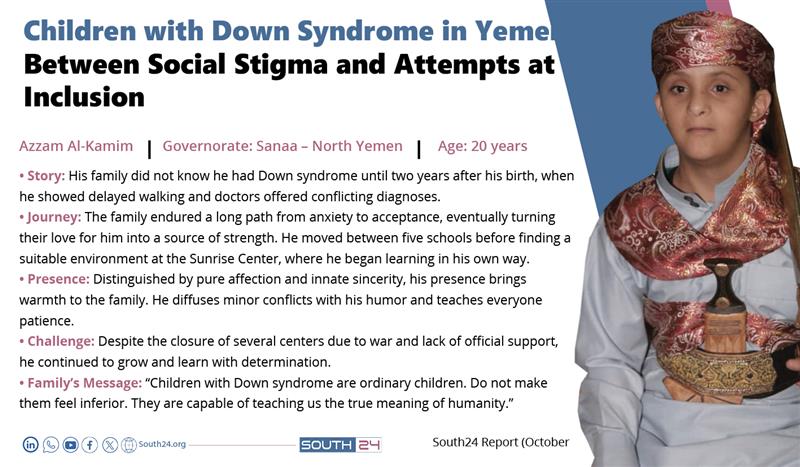

Azzam: When love Triumphed over Social Judgment

From Sanaa, Azzam Al-Kamim was not an ordinary child. He was a special note in the melody of life, as his family describes him.

Azzam was born surrounded by love, but his journey began with anxiety and questions. His mother says the family did not know of his Down syndrome until two years after his birth, when his walking was delayed and doctors offered varied explanations: “brain atrophy, glandular dysfunction, or natural delay.” Then came the truth that changed their outlook on life entirely.

His father told South24: “We were deeply affected at first, but over time we realized that God had given us a new reason to love.”

The family learned that difference is not a flaw, but another path to understanding and existence. Nevertheless, schooling was not easy. Azzam moved between five schools in search of an accepting environment, until he found the Sunrise Center -- a place that understands him and allows him to learn in his own way.

Despite the closure of several centers due to the war and scarcity of official support, Azzam’s growth continued. Today, he is twenty years old. As for his family, their dream is simple yet profound: that he is able to live with dignity, becomes self-reliant, and finds in society a space for his intelligence and talent.

Centers between Constraint and Aspiration

In the absence of clear domestic policies toward people with intellectual disabilities, rehabilitation centers in Yemen stand as small islands of hope amid a sea of neglect. They operate through self-driven efforts and intermittent contributions, and strive —with modest tools—to grant children with Down syndrome their right to education and normal life.

In Sanaa, the Sunrise Center for Autism and Intellectual Disabilities is an example of this daily struggle. Maryam Al-Ansi, the center’s director, told South24: “At the Sunrise Center, we want our work to be based on solidarity, and shared responsibility with the community. Our motto is ‘Hand in Hand’.”

The center receives a number of children with Down syndrome. It offers comprehensive programs that include occupational therapy, speech and language sessions, training in self-reliance (personal hygiene, dressing, manners), and academic education up to the fifth grade.

But these efforts have to contend with recurring obstacles. In the absence of an educational curricula tailored to this group in Yemen, the center is forced to adapt the general syllabi to the children’s needs and add activities and educational games to make the process more interactive and enjoyable.

Al-Ansi adds that all teachers at the center are graduates in psychology and special education. They undergo training courses every three months to develop their skills in dealing with different cases.

Al-Ansi highlights another challenge no less important: the specific health needs of children with Down syndrome, such as hypersensitivity, enlarged tongues, and some cardiac or dermatological issues. Keeping in mind their health vulnerabilities it becomes essential to maintain hygiene and continuous sterilization of the center for their safety.

Economic Factors

The suffering of children with Down syndrome in Yemen cannot be separated from the deteriorating economic reality of the country that touches every household and service. Poverty here does not produce deprivation alone; it increases disability and makes it harsher. In a country where millions live at the edge of subsistence, the idea of specialized care or psychological rehabilitation becomes a distant luxury.

Economic journalist Wafiq Saleh told South24 that the collapsed economic situation is the most influential factor in depriving children with Down syndrome of their rights.

He added: “Today, more than 80% of the population lives below the poverty line, which means that most families are barely able to secure their basic needs. How can they be expected to provide the costs of treatment or rehabilitation sessions or special education for children who need continuous support?”

Required Interventions

Wafiq Saleh points out that weak government spending on social protection sectors and inclusive education, in addition to the lack of stable policies, has exacerbated the isolation of children with Down syndrome. In stable countries, the state bears a large part of the costs of care and rehabilitation, while in Yemen families are left on their own to face a burden beyond their capacity, often forcing them to give up their child’s right to treatment or education for financial reasons.

Saleh believes that addressing the crisis cannot be achieved through partial solutions—opening a center here or a media campaign there—but must begin with broader economic reforms that restore a minimum level of stability and redirect support toward the most vulnerable groups.

For his part, disability rights activist Abdullah Banyan notes that the absence of sustainable policies makes centers specializing in handling Down syndrome operate according to a “continuity by chance” logic, relying on external grants or seasonal donations that neither ensure operation nor development.

He added to South24 that weak government budgets and the halt of local funding channels have created a financial gap that threatens to close dozens of centers that represent a lifeline for children with Down syndrome.

Banyan believes that overcoming this reality requires a comprehensive institutional transformation through adopting a national strategy for the rights of persons with disabilities and children with Down syndrome that sets clear foundations for sustainable financing, and obligates the relevant ministries to allocate annual budgets within the state’s general plan.

He also calls for the establishment of a specialized government unit devoted to monitoring rehabilitation centers and providing necessary technical and financial support, alongside launching continuing training and qualification programs for workers and teachers to improve the quality of services provided to children.

The insights provided by specialists reveal that the challenge facing children with Down syndrome in Yemen does not lie only in the lack of social awareness, but also in the absence of public policy that guarantees inclusion and care as a right, and not a favor.

The stigma that begins within the family increases with institutional absence. Initiatives born of hope die at the first funding shortfall, while centers turn into solitary lines of defense in the state’s absence.

Nevertheless, stories like Abdulwahid and Azzam stand as living testimonies that human will can compensate for policy failures. This calls for greater attention to this segment of society and leveraging occasions such as World Down Syndrome Day (March 21) as a continual reminder of the importance of integrating them into normal life.

Previous article