A Hadhrami child from Ghayl Bin Yamin suffering from nasopharyngeal cancer. In the background, local residents inspecting water which appears to be mixed with oil pollutants in Sah district of Hadramout governorate (Designed by ‘South24 Center’)

Last updated on: 03-06-2025 at 10 AM Aden Time

|

|

Investigative report by Abdullah Al-Shadli (South24)

In a village located within Sah district of Hadramout governorate, young Layla would spend her days playing around the nearby farms. Her family relied on a water well for drinking and irrigation, located not far from the sites affiliated with oil companies operating in the area. Like many other rural families, Layla’s family lacked environmental awareness about the potential dangers this water could pose. What mattered to them was the water’s availability and accessibility and that its taste seemed harmless.

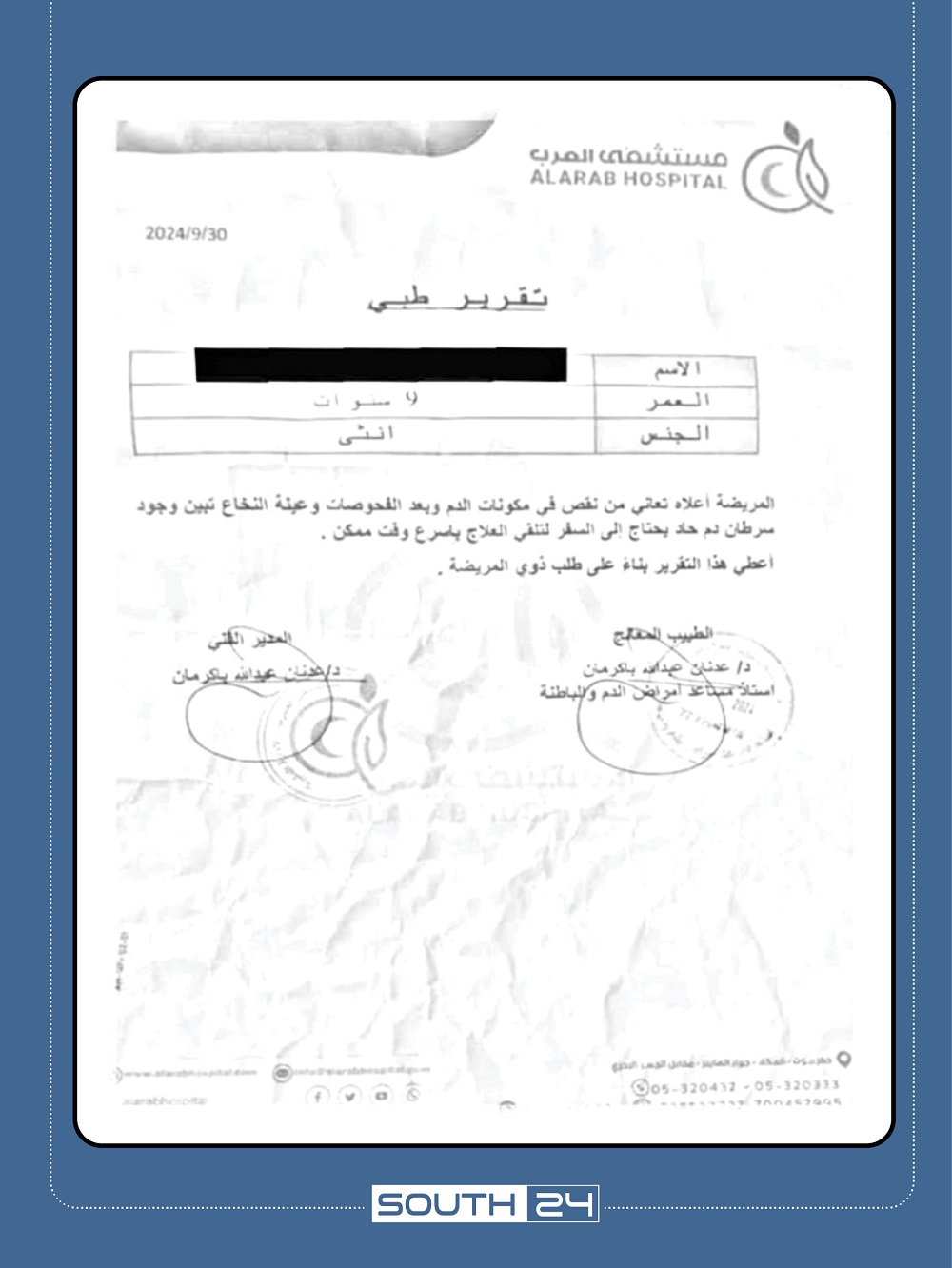

However, one morning in September 2024, Layla lost consciousness, and fell into a coma that no one could explain. After a series of medical tests, the shocking diagnosis was disclosed: that she suffers from acute leukemia. Layla needed to urgently travel abroad for treatment but her family lacked both the means and the time. This was just the beginning of a tragedy that continues to unfold in the oil concession areas of Hadramout, where the suffering of residents intersects with the hidden consequences of oil extraction activities.

A medical report of Layla, September 30, 2024 (provided to ’South24 Center‘ by the child's family).

Layla's brother, Salem, told ’South24 Center‘: "We used to drink from this same well for years. None of the relevant authorities, including from the state and the oil companies, ever told us that this water might be contaminated or that being near to oil facilities could mean exposure to the risk of a slow death."

The matter is no longer limited to a single case, as it has taken on a systemic nature. Similar cases to Layla’s have emerged in other districts like Ghayl Bin Yamin and Al-Dhalea, where different types of cancers are being detected among children, women, and men of different ages. At the same time, there is no healthcare infrastructure capable of tackling the situation. Furthermore, there is no preventive medical intervention nor any environmental oversight to match the scale of the oil activity. This stirs a pressing question: Have oil extraction operations in Hadramout, through the water, air, and soil pollution they produce, turned these areas into health-hazard hotspots?

Over a period of six months between November 2024 and April 2025, ‘South24 Center’ journalist Abdullah Al-Shadli prepared this investigative report

General Background

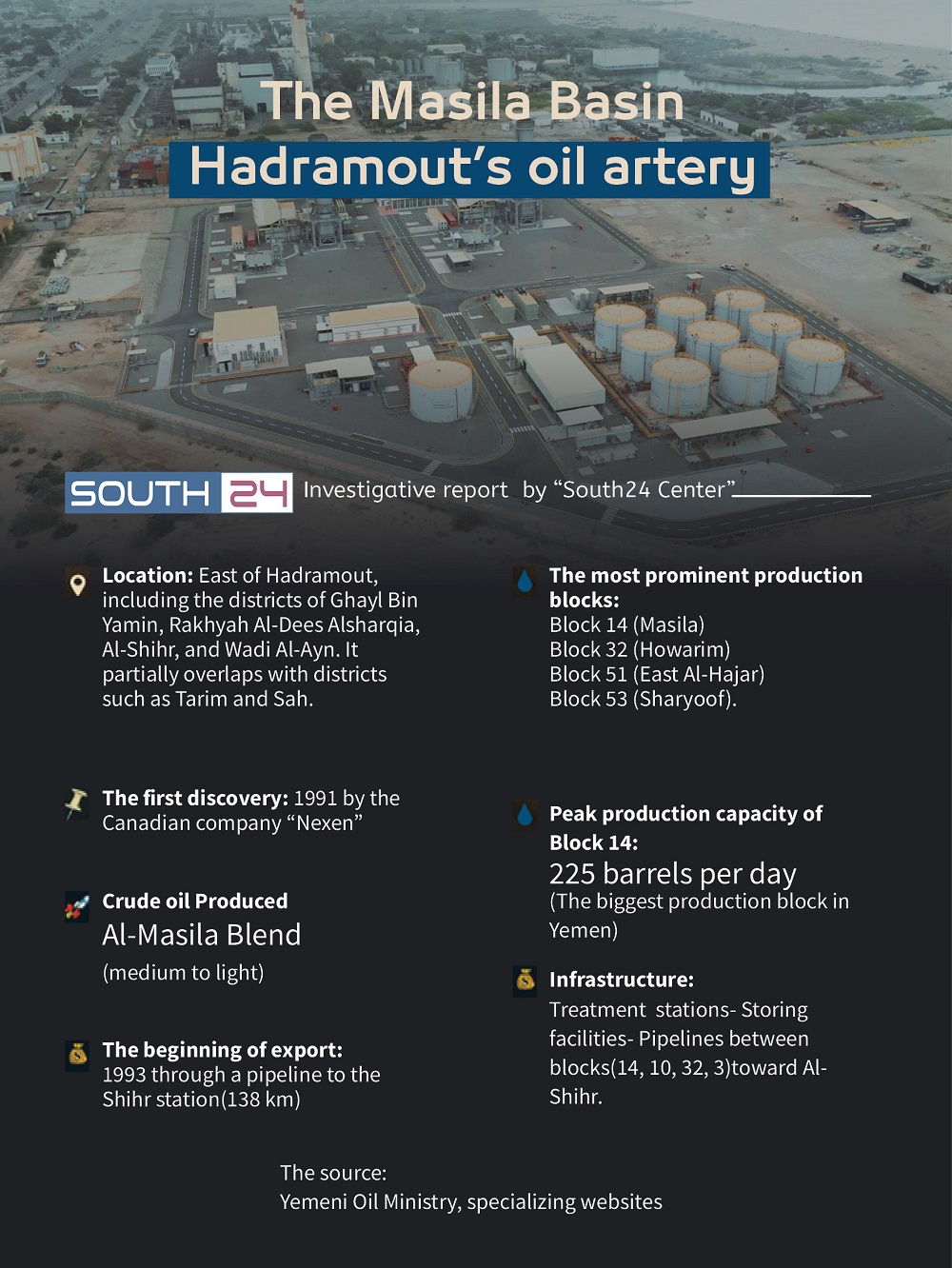

Hadramout occupies a pivotal position in the oil production map of South Yemen. It has the largest oil fields in the country within what is known as the ’Masila Sedimentary Basin‘, located in the eastern part of Hadramout. This basin is considered one of the richest geological basins in hydrocarbons in the country. Geographically it covers a wide area that includes several districts, most notably Ghayl Bin Yamin, Rakhyah, Al-Dees Alsharqia, Al-Shihr, and Wadi Al-Ayn. It partially overlaps with districts such as Tarim and Sah. These areas include the operational concessions known as production blocks, such as Block 14 (Masila), Block 32 (Howarim), Block 51 (East Al-Hajar), and Block 53 (Sharyoof).

The real oil discovery in Al-Masila began in 1991 by the Canadian company Nexen. The field saw its first production in 1993 through a pipeline extending about 138 km to the Shihr (Dabba) Terminal, which serves as the main outlet for exporting crude oil from Hadramout to global markets. During its peak activity in the early 2000s, Block 14 alone produced around 225,000 barrels per day, making it the biggest in the country. The block includes multiple fields, most notably: Al-Sunnah, Al-Hajjah, and Al-Kamal, characterized by its medium to light crude oil known as the ’Masila Blend’.

The scope of the Masila Basin is not only geographical, but technically consists of a network of advanced oil infrastructure facilities, including separation and treatment stations, storage units, and pipelines that interconnect various production blocks such as blocks 14, 10, 32, and 53, extending to the port city of Al-Shihr. This basin has served as a vital economic engine for Yemen, accounting for approximately 80% of the country's oil exports, prior to the conflict. It remains the primary conduit for oil exports under the control of the Yemeni government.

Demographic Context

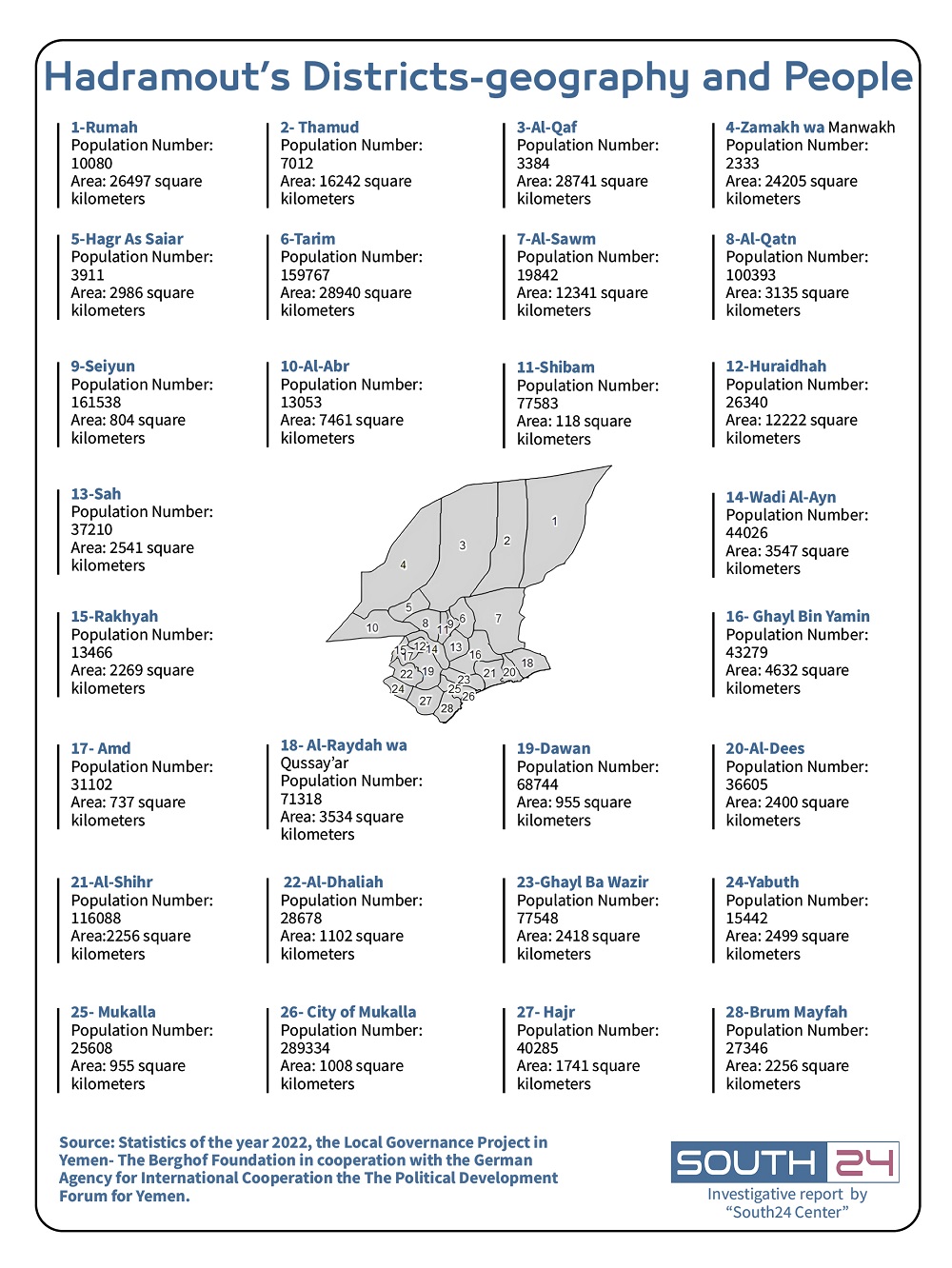

Hadramout is Yemen's largest governorate, covering an area of 191,000 sq km, which constitutes about one-third of the nation's total landmass. The governorate is administratively divided into 28 districts, featuring diverse geographical landscapes, including coastal areas, valleys, and deserts. This enhances its strategic and economic significance. As of 2011, its population was estimated at 2.25 million with the populace concentrated in urban districts and valley regions, while the vast desert districts have lower population densities.

The city of Mukalla is the district with the largest population at 289,334. The city also serves as the administrative and economic hub of Hadramout. It is followed by Seiyun and Tarim districts in Wadi Hadramout, with a population of around 160,000 each. They play a key religious and commercial role in the region. Al-Qatn District extends over a large area of 3,135 sq km, with more than 100,000 residents. Shibam is notable for its high population density within a compact area of 118 sq km. On the coast, Al-Shihr and Ghayl Ba Wazir are historically and agriculturally important, each with a population of around 75,000.

On the other hand, districts like Rumah, Thamud, and ’Zamakh wa Manwakh‘ cover vast areas, some exceeding 20,000 sq km, but are home to only a few thousand residents. This reflects the developmental challenges facing these remote areas. This disparity in population density and geographic distribution highlights the need for a balanced development policy to enhance resource investment and redistribute public services in line with Hadramout’s strategic importance as an economic hub, as a diverse population center, and as a crucial point of balance on the country’s map.

Companies and Production

Hadramout has witnessed significant changes in the landscape of oil companies operating there since the start of oil production in the early 1990s till the present day. The story began in 1987 when Canadian Occidental Petroleum, which later was renamed ’Nexen‘, acquired Block 14 (Al-Masila) (Nexen is now known as CNOOC Petroleum North America ULC, after being bought by Hong Kong–based CNOOC Limited in 2013). In 1991, the Canadian firm announced the first major commercial discovery in the ’Sona‘ field, marking a real breakthrough for the oil sector in Hadramout .

In the 1990s, the map of companies operating in Hadramout expanded. The French company ’Total‘ became prominent through the Block 10 concession in eastern Shabwa, which is technically managed as an infrastructure linked to the Al-Masila fields. The company discovered several fields including Kharir, Atuaf, and Wadi Taribah, and their production was linked to the infrastructure of Block14. In 1999, the Norwegian company DNO joined the oil scene after discovering oil in Block 32 (Hawarem) and began production in 2001. DNO also participated in the development of Block 43 and Block 53 (Sharyoof), in cooperation with the British company Dove Energy which managed the Sharyoof field since 2002.

On the other hand, the Canadian company ’Calvalley Petroleum‘ entered Block 9 (Malik) in the western region of Hadramout and managed to started production in late 2005. These companies operated under Production Sharing Agreements (PSAs) with the Yemeni government. By the second decade of the 21st century, the Yemeni government began moving toward regaining control of its key oil assets. In November 2011, it refused to renew Nexen’s contract after 20 years of operating Block 14 and transferred its operation to a new national company called ’Petro Masila’, which has since become the main operator of Yemen’s largest oil fields.

The year 2015 and the following years witnessed unprecedented turmoil after the outbreak of war, prompting most foreign companies to declare ‘force majeure’ (a clause that frees both parties from liability or obligation when an extraordinary event or circumstance beyond their control prevents one or both from fulfilling their contractual obligations) and leave the country. These companies included Total, Calvalley, DNO, and OMV. Most oil production and export operations came to a halt, foreign staff were evacuated, and maintenance and technical oversight became lax.

In May 2017, after the Port of Al-Shihr was retaken from the clutches of the Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) with support of the Hadramout Elite Forces and the Arab Coalition, PetroMasila gradually resumed oil production. By 2017, the company effectively controlled operations in blocks 14, 10, 51, and 53. DNO and Calvalley maintained only nominal concession rights without actual operational presence. PetroMasila sometimes cooperated with its former partners as technical consultants.

Blatant Violations

Since production began in Block 14 (Al-Masila) in 1993, operating companies have relied on conventional drilling techniques using vertical and deviated wells at depths ranging from 1,500 to 2,500 meters, targeting Cretaceous sandstone reservoirs (‘Qishn‘ formation’) above Jurassic source rocks. In the early years, the wells flowed naturally, but by the mid-2000s, signs of depletion began to emerge.

By 2008, the Canadian company Nexen recorded an associated water percentage exceeding 95% of total production in some of the Al-Masila wells. This means that out of every 100 barrels pumped less than five barrels were pure oil. In some Al-Masila facilities, the volume of daily treated water reached more than two million barrels, placing enormous pressure on the separation and treatment facilities.

Oil pollutants being discharged illegally in Al-Ghubaira, Wadi Al-Masila, Hadramout, February 2014 (Exclusive photo for South24 Center)

As part of investigating the environmental impact of the oil industry in Hadramout, corroborating testimonies have emerged to reveal blatant violations committed by the oil companies operating in the sector, chief among them Canadian ‘Nexen’.

In this context, geological engineer Emad Bamsdos, who worked as a supervisor for UNICEF on an artesian water well drilling project in Al-Dhalea district (his hometown) in 2018, said that ’Nexen‘ carried out an acid injection operation in Al-Masila’s oil wells a few years before exiting Yemen. He explained that while the purpose of this operation was to boost oil production, the large quantity of acid used “led to a temporary increase in oil production before leading to the destruction of the wells and severe environmental damage”.

Bamsdos told ’South24 Center‘ about the toxic emissions resulting from crude oil spillage onto the soil. He confirmed that these operations release hazardous gases such as methane, ethane and propane, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (BTX) which are directly linked to respiratory cancers. He also pointed out that hydrogen sulfide gas emitted from these operations could, if inhaled at high concentrations, cause brain paralysis or even death, in addition to the contamination of groundwater with radioactive and saline elements.

To delve deeper into the environmental risks related to oil extraction operations, the ‘South24’ author consulted chemical engineer Amer Ahmed, who has served as project supervisor for several international organizations, including the UN World Food Programme (WFP), and who previously worked at PetroMasila. Engineer Ahmed told ’South24 Center‘ that one of the main sources of oil pollution in extraction areas is the unregulated use of fluids and chemical additives in drilling operations.

Ahmed explained that these substances primarily include drilling fluids, calcium carbonate, and lubricants, all considered common environmental pollutants at oil sites. He referred to a field incident in one of the villages of Tarim district, where these substances were disposed of unsafely following exploratory drilling operations. He said, "Instead of handling them safely, they were dumped in pits not designed to contain such substances, leading to their seepage into the underground soil and water."

Engineer Ahmed informed that due to the lack of isolation and environmental treatment procedures, these hazardous chemicals began to surface between 2012 and 2018 at depths ranging from 40 to 60 meters below the surface, leading to noticeable contamination of groundwater. "At first, some thought this waste was crude oil, but it turned out to be drilling waste."

Environmental expert Abdulqader Al-Kharraz provided a more comprehensive picture of the long-term impact of these activities in the oil concession areas. Al-Kharraz told ’South24 Center‘ that unsafe reinjection operations are among the most prominent environmental threats in oil concession areas, especially in Hadramout. He pointed out that in Hadramout oil wells water accompanies the oil “unlike in other areas like Marib, where the byproduct is gaseous”.

Al-Kharraz voiced concern over the continuing use of wrong methods to handle this water, and explained that “these methods are outdated and have now become environmentally harmful”.

According to Al-Kharraz, the problem is exacerbated due to the presence of “hazardous hydrocarbon components in the produced water, in addition to drilling waste and chemicals used in drilling operations”, all of which causes severe soil and water contamination. He added, “In some cases, this water was directly dumped onto the soil, leading to significant contamination in many areas of Hadramout.”

Oil pollutants flowing from a water spring near Oil Sector 10, Al-Ghubaira area, Wadi Al-Masila, Hadramout, October 2014 (Exclusive photo for South24 Center)

These practices leave their disastrous impact on the agricultural and water sectors. Al-Kharraz noted that the resulting pollution “leaves its long-term negative impact on the soil and groundwater, damaging agricultural lands and crops”. He emphasized that “the irrigation water used in these areas undergoes changes in its properties and becomes contaminated, which affects its quality. The impact of the contamination is not limited to crops as the same water is often used for the livestock causing harm to the animals raised on these lands”.

Talking about the direct health impact, Al-Kharraz pointed to the noticeable “spread of cancer in oil-producing areas such as Hadramout, Shabwa, and Marib”, and stressed that this “is directly linked to the oil industry which is considered the primary source of such diseases in these areas”. He added that “there are no other industrial facilities affecting the area in this way” and highlighted the urgent need to responsibly manage oil waste.

From the scientific perspective, there is supporting evidence linking oil exposure to cancer based on scientific data and expert opinions. In April 2021, the US National Library of Medicine published a study by researcher F.M. Onyije titled ’Cancer Incidence and Mortality Among Petroleum Industry Workers and Residents Living in Oil-Producing Communities’. The study concluded that proximity to oil production facilities is associated with an increased risk of blood cancer, especially among children. The study also monitored high mortality rates in areas experiencing continuous oil activity.

Solid oil pollutants near Oil Sector 10 – Al-Ghubaira, Wadi Al-Masila, Hadramout, February 2014 (Exclusive photo for South24 Center)

Victims’ Stories

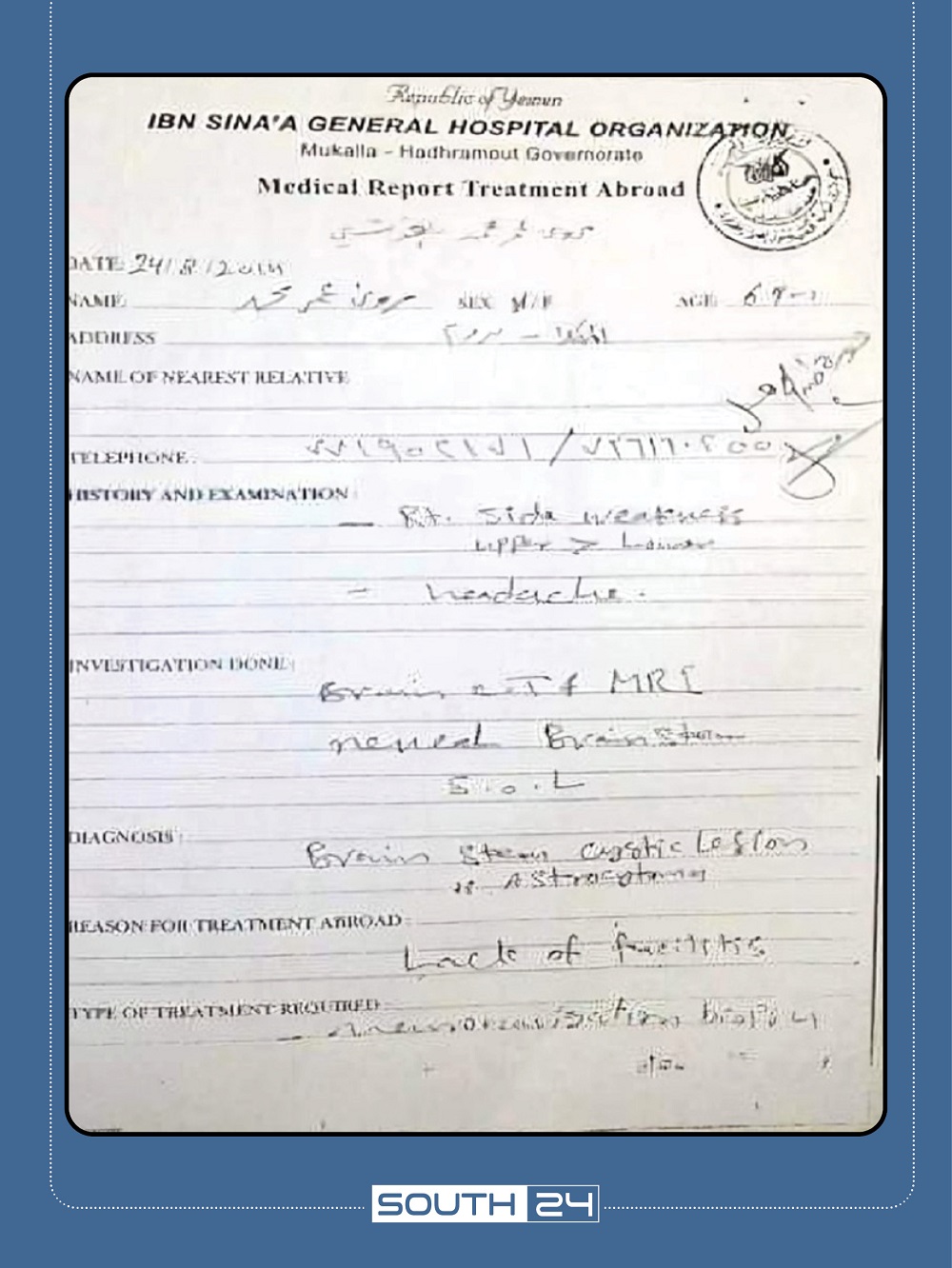

In the Ghayl Bin Yamin district, east of Mukalla city, six-year-old Marwa was standing in front of her small mirror when her father noticed an abnormal swelling on one side of her head. At first, he thought it was a minor inflammation. However, she soon began to suffer from severe headaches and vomiting spells. In August 2014, after a series of examinations conducted at Mukalla Hospital, it was revealed that Marwa had a malignant brain tumor. Her father, Omar Mohammed, began a long journey of chemotherapy to ease his daughter’s pain but her response to the treatment was slow.

The family had no health insurance and there were no official bodies willing to cover the high costs of treatment. Therefore, Omar had to sell small family possessions to cover the expenses. Omar doesn't hesitate to hold the oil companies operating in the surrounding area directly responsible, primarily the Norwegian DNO, Canadian Nexen, and parts of Total’s sector extending between Hadramout and Shabwa. Omar told ’South24 Center‘ that the emissions and leakage resulting from their operations are the cause of his daughter’s illness and of most other cases appearing in the region.

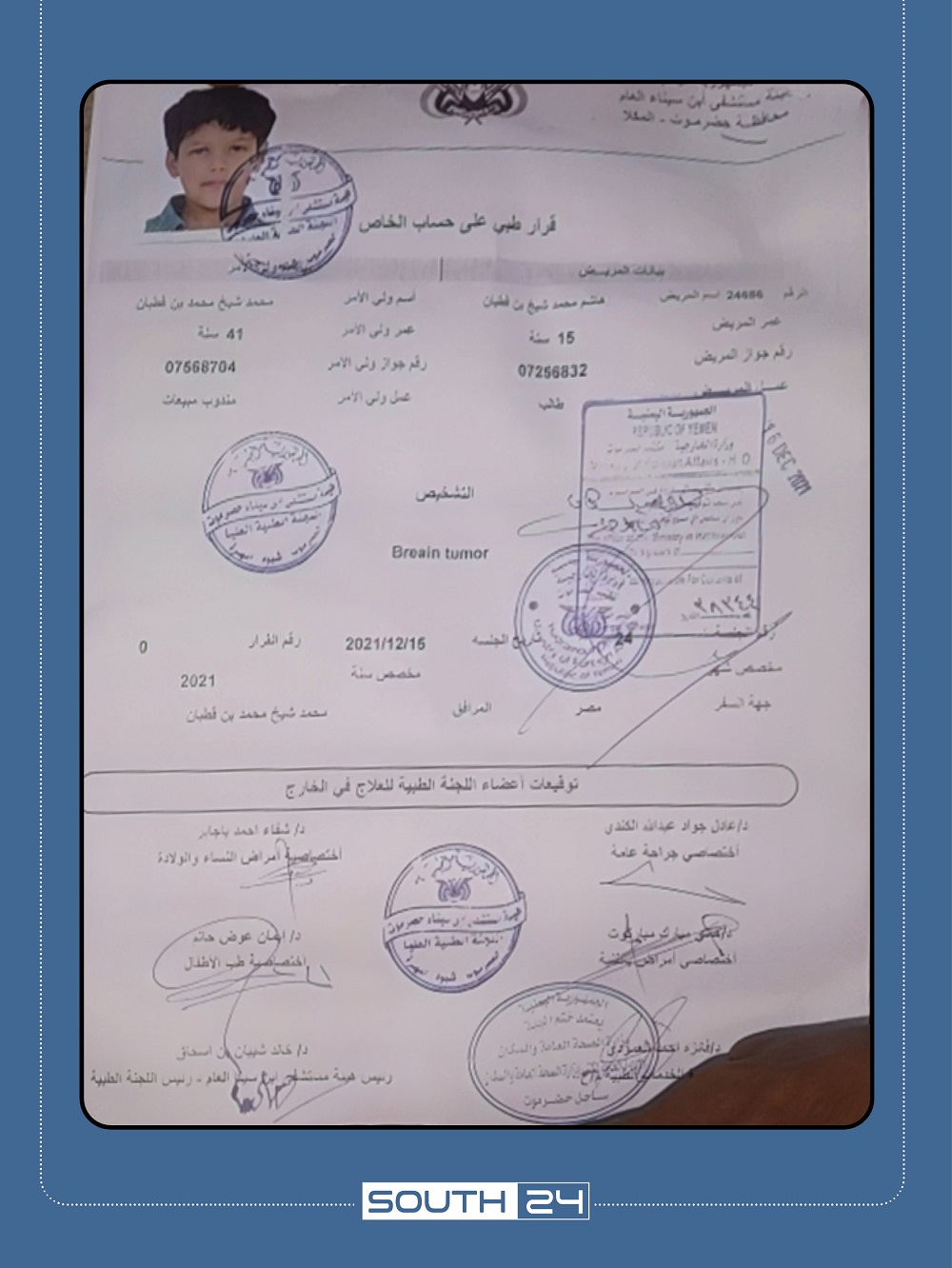

Medical Report for the child Marwa, August 24, 2014 (Provided to ’South24 Center‘ by the child’s family)

The same story repeats in Dhliaah, the home of Mohammed Baqtian, father of a 15-year-old boy named Hashem. In December 2021, he noticed changes in his son’s movement and recurring difficulties with his speech and balance. Within weeks, local medical reports confirmed that Hashem had a brain tumor. They have received no assistance from any government or oil-related entity for his treatment, despite living within the oil concession area.

Baqtian said the family was forced to sell their house, women’s jewelry, and everything they owned to cover the costs of the treatment and travel between Seiyun and Aden. He added that what makes the tragedy worse is the sense of isolation as no psychological, medical, or legal support is provided to the families of those similarly afflicted. It was as if the cancer that came from beneath the earth is no one’s responsibility.

Medical Report of the child Hashem, December 15, 2021 (Provided to ’South24 Center‘ by the child’s family)

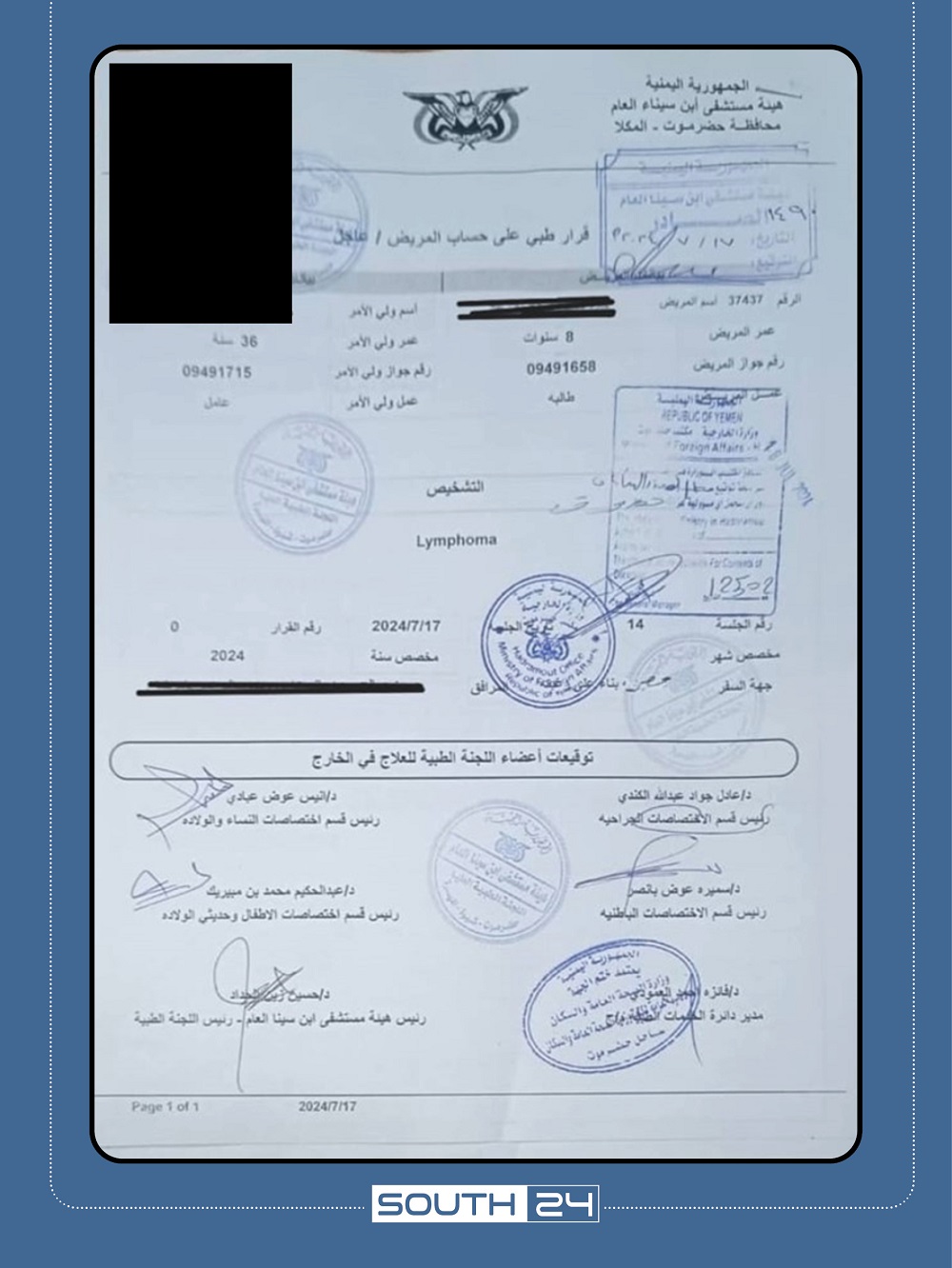

In another documented case from Ghayl Bin Yamin, a medical report issued by a government hospital in July 2024 confirms that an eight-year-old child was diagnosed with cancer of the pharynx and lymphatic system.

The ‘South24 Center’ author didn’t disclose the child’s identity at the request of the family to maintain privacy. The medical document reveals the extent of the spread of the disease amongst the most vulnerable age group. The child had no prior health issues and no family history of the disease, strengthening the hypothesis of the disease being linked to environmental factors.

Medical Report of the child diagnosed with pharyngeal and lymphatic Cancer – July 17, 2024 (Provided to ’South24 Center‘ by the child’s family)

The Numbers

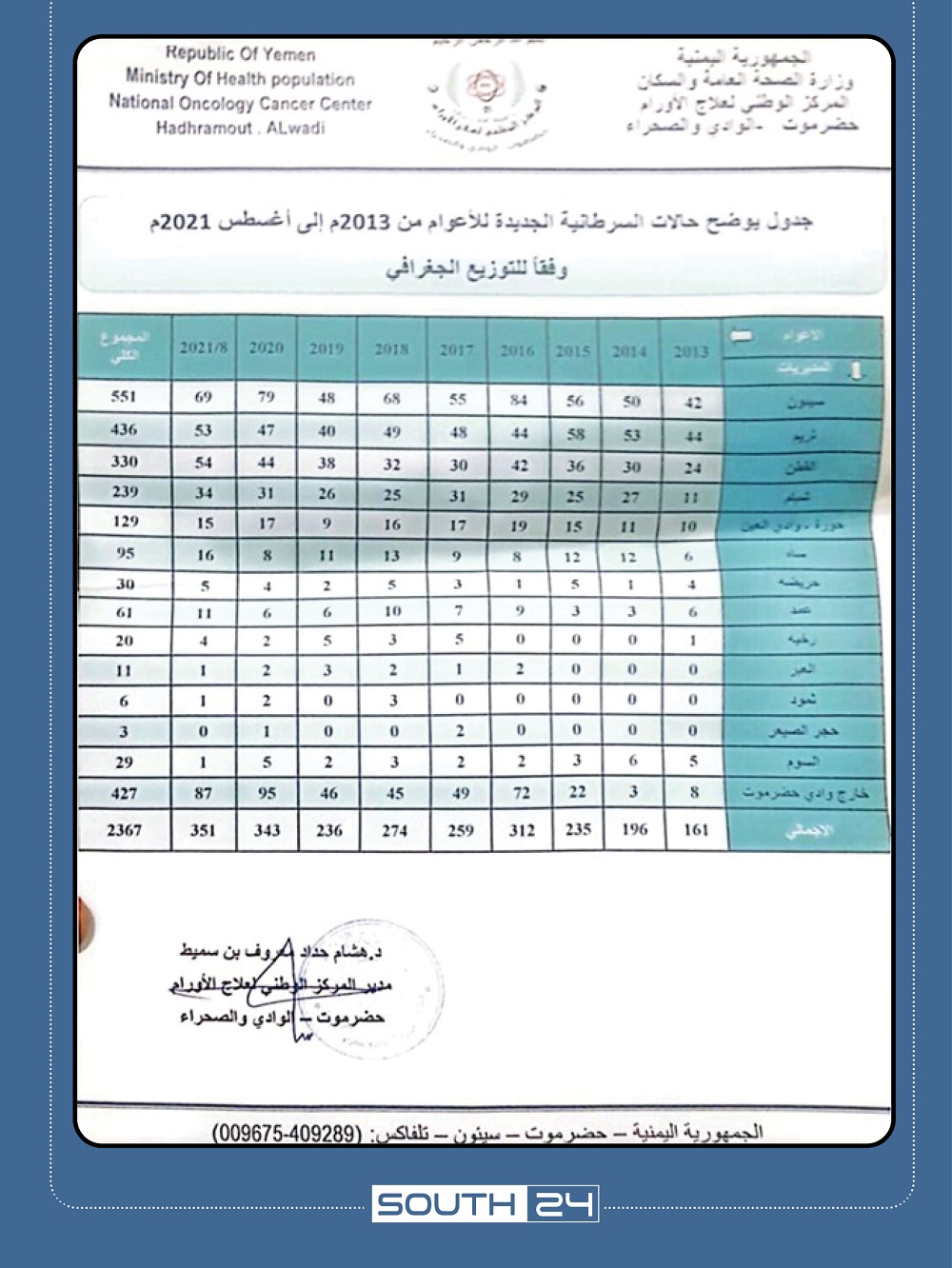

Official data obtained by ’South24 Center‘ from the National Oncology Cancer Center in Wadi Hadramout indicates a worrying rise in cancer cases between 2013 and August 2021. In 2013, there were 161 recorded cases. The number gradually rose over the following years to 189 cases in 2014, then jumped to 259 in 2015, and reached 312 cases in 2016. This accelerating surge stirs fundamental questions about the environmental and health-related causes, especially given the expansion of oil industry activities in the region in recent decades.

A table showing new cancer cases from 2013 until August 2021, based on geographic distribution, according to statistics from the National Oncology Cancer Center – Hadramout Valley and desert.

Despite this noticeable rise, 2017 saw a slight drop to 259 cases, then a rise again to 274 cases in 2018, followed by a decline to 236 in 2019. However, this decrease does not necessarily denote real improvement; rather it may reflect the poor diagnostic capabilities and lack of early screening. Moreover, it could also denote the impact of the conflict conditions on the health services.

By 2020, the numbers began to rise again sharply, with 343 cases recorded in that year alone. The first eight months of 2021 saw about 351 cases, marking a peak during the entire period.

Geographically, the highest rates during the period were recorded in the districts of Seiyun (551 cases), Tarim (436), Al-Qatn (330), Shibam (239), and Sah (95). This is partly linked to population density but also raises questions about the proximity of these areas to oil concession sites and waste disposal operations. Remarkably, 427 cases to the oncology center came from outside the valley of Hadramout, reflecting that the center receives cases from other governorates, which increases the pressure on its limited resources.

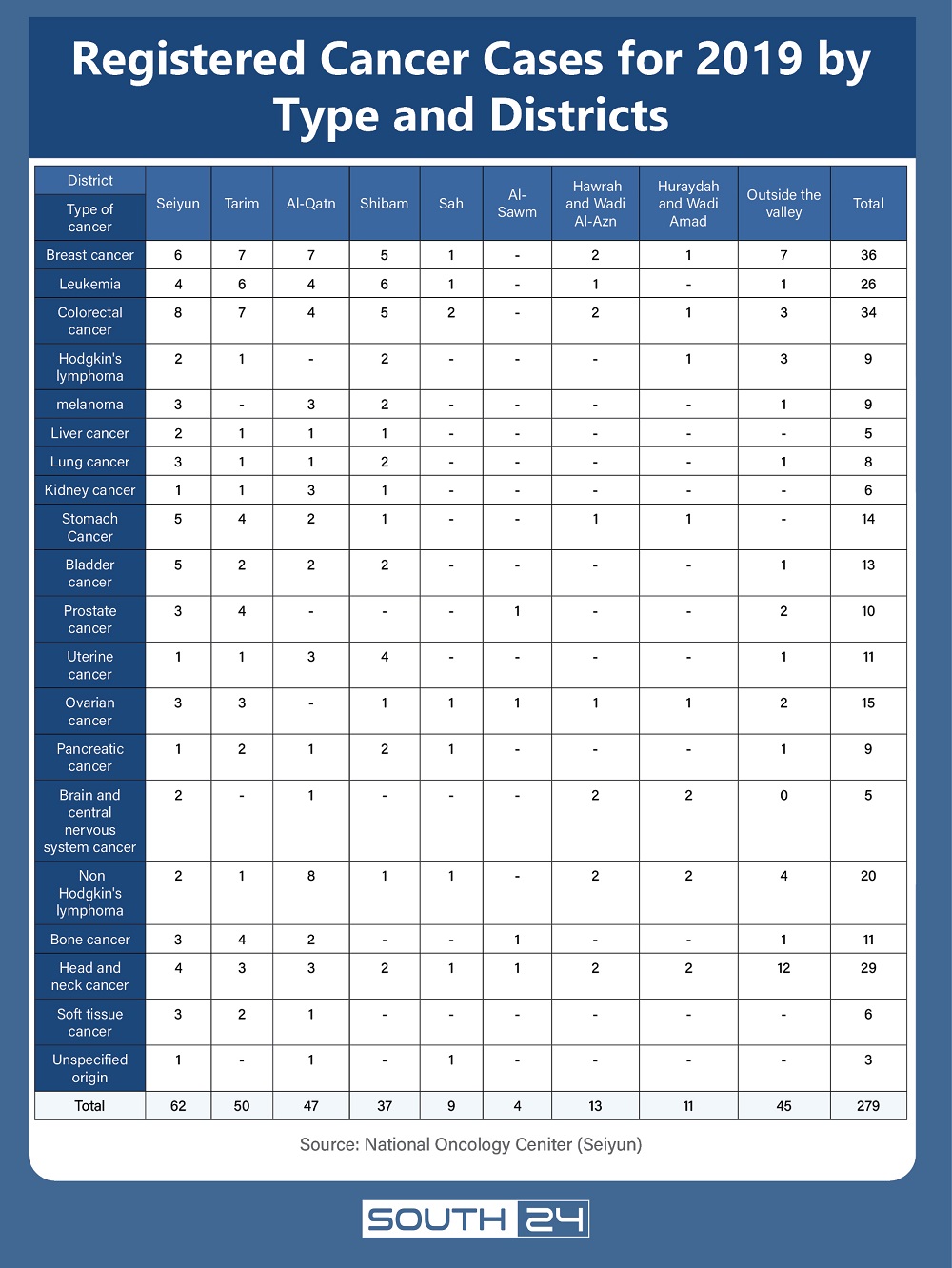

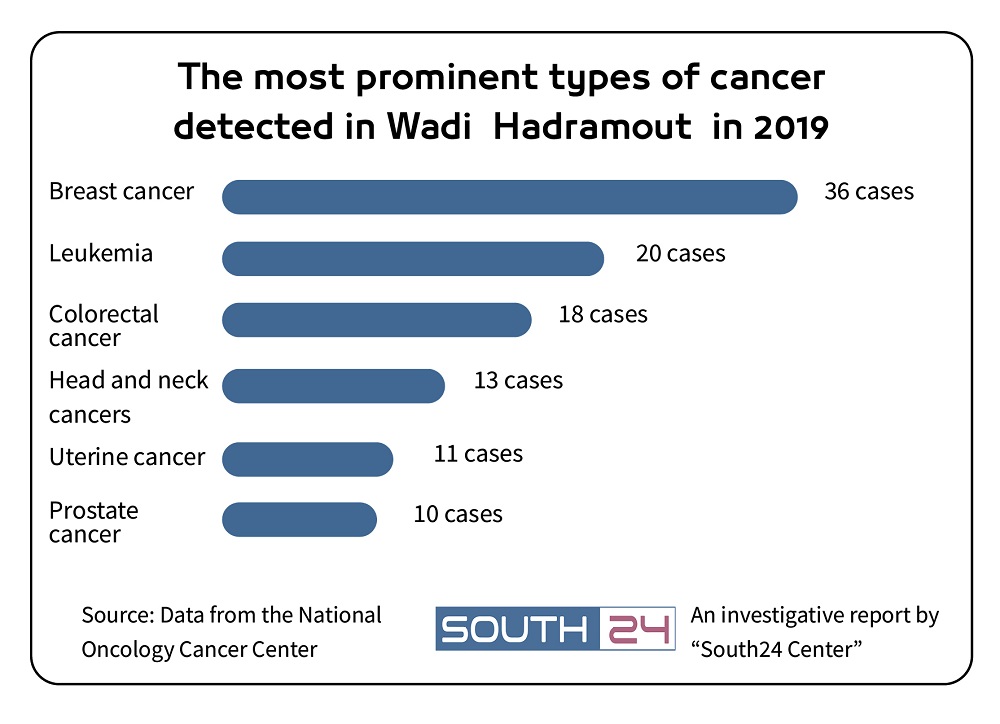

Official data issued by the National Oncology Cancer Center for the valley and desert of Hadramout for 2019, obtained by ’South24 Center‘, shows that cancers in the region are distributed in a pattern, highlighting the healthcare gaps and intervention priorities. Breast cancer topped the list with 36 registered cases, making it the most common type, especially among women. This figure reflects the absence of regular early

screening programs, raising questions about community awareness and the lack of preventive health coverage, particularly in rural districts.

Cancer cases recorded in 2019 by type and district, according to statistics from the National Cancer Treatment Center – The valley and desert of Hadramout.

The statistics reveal that colorectal cancer ranks third with 18 cases, followed by head and neck cancers with 13 cases, and prostate and uterine cancers with 10 and 11 cases respectively. There is a noticeable increase in stomach, bone, and bladder cancers, while fewer cases were detected of liver, kidney, and skin cancers. This diversity in cancer types and their geographic distribution raises deep questions about the dietary patterns, water quality, and the extent of the impact of industrial and oil activities on people’s health.

The statistics covered 13 districts in Wadi Hadramout, with the largest share of cases seen in the districts of Seiyun, Tarim, and Shibam. This reflects the population density on one hand, and perhaps also the proximity of some areas to industrial activity sites or oil waste disposal zones.

Specialists who spoke to ’South24 Center‘, such as oncology expert Mohammed Awad Al-Shanini, who hails from the oil-rich Gayl Bin Yamin area, believe that the numbers of cancer and other serious disease cases in Wadi Hadramout in particular are much higher than what is reported by the oncology centers affiliated with the Ministry of Health. He believes that the numbers might be larger due to the absence of early diagnosis, some patients traveling outside the governorate for treatment without official registration, or dying before reaching specialized centers.

He pointed out that cancer is often diagnosed only at the advanced stages, which makes the official statistics a pale reflection of the actual scale of the crisis.

Local residents inspect water which appears to be mixed with oil pollutants after drilling an artesian well – March 2018, Ghayl Omar, Sah district, Hadramout (Source: activists)

Absent Justice

In Hadramout, environmental responsibility is not equitably distributed among the stakeholders, but instead silence and complicity prevail. The oil companies, which have amassed huge daily profits from beneath the earth, would leave their sites at night without accountability, leaving behind waste of unknown fate. No environmental data is regularly published nor are there any transparent reports clarifying the waste disposal methods or the chemicals used in the drilling and production.

At the official level, the Yemeni Oil Ministry has seen more than one minister being appointed in recent years, including some belonging to Hadramout itself. However, the ministry hasn’t taken any stand or issued any report to address the environmental degradation in the oil concession areas. This official silence not only reflects poor oversight but also a lack of political will to open this file or even discuss it publicly. Geologist engineer Emad Bamsdos said: "I cannot imagine that three ministers from Hadramout took charge of the Oil Ministry without being aware of the irresponsible environmental practices in their regions. Were they ignorant or were they deliberately ignoring the crisis? “

A flood channel (seasonal riverbed) near Oil block Sector 10, Al-Ghubaira area, Wadi Al-Masila, Hadramout governorate, February 2014 (Exclusive photo for ‘South24 Center’)

Environmental expert Dr. Abdulqader Al-Kharraz confirms that oil facilities in Hadramout have not taken any effective environmental measures in recent years. He pointed out that waste is buried directly in the surrounding lands, and that contaminated water is discharged into the fields and the gases are released into the air without treatment or monitoring. According to him, these companies “bear no moral or social responsibility towards the local residents, but rather treat the areas as mere operational sites, with no commitment or accountability for the lasting damage they cause”.

As part of professionalism and in order to present the other side of the case, ’South24 Center‘ contacted several government and oil entities while preparing this investigative report about the environmental and health effects of oil extraction operations in Hadramout, including the Yemeni Ministry of Oil, the Yemeni Ministry of Health, the Environmental Protection Authority, the Petroleum Exploration and Production Authority, PetroMasila Company, and the Governor of Hadramout. Official mails were sent in mid-April 2025 requesting for interviews and clarifications regarding the evidence uncovered by the investigation team about the environmental pollution and the notable rise in cancer rates in the oil concession areas.

The messages sent to these entities focused on the role of each in oversight and remediation. ’South24 Center‘ set a one-week deadline for responses, affirming its commitment to transparently publish the official views. However, none of the aforementioned parties had responded till the time of publication.

The report’s author also contacted three major international oil companies that have operated in Wadi Hadramout, including Norwegian DNO, Canadian Nexen, and French TotalEnergies during the same period, seeking official responses to allegations of environmental violations connected to their past operations in the region. As of the time of publication of this investigative report, no responses were received from these companies.