Captain Haines (Archives)

آخر تحديث في: 19-11-2025 الساعة 3 مساءً بتوقيت عدن

|

|

Fatimah Johnson (South24 Center)

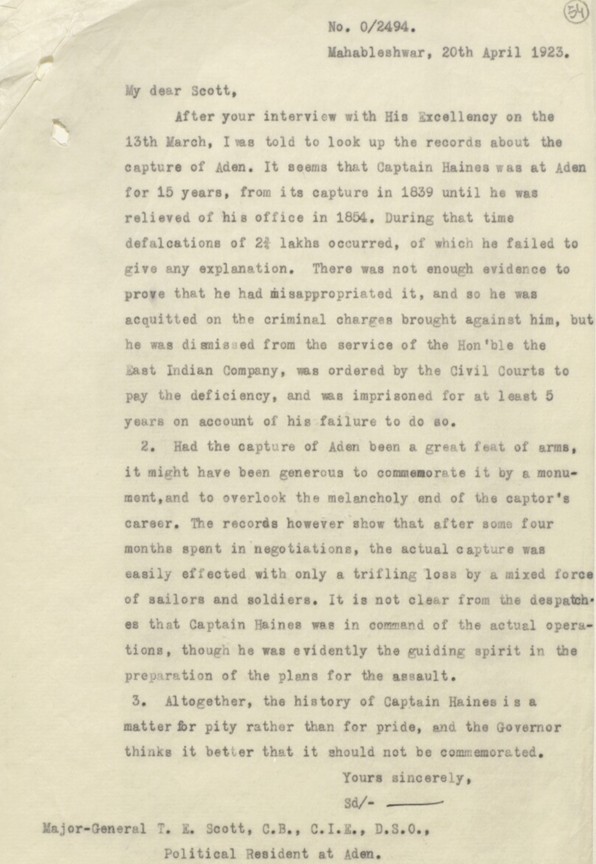

As the centenary approached marking British supremacy in Aden, the Government of British India moved to suppress official celebration of the career and life of Captain Stafford Bettesworth Haines. Haines is normally credited for the successful action that led to the occupation of Aden. However, in many historical works he is given no more mention than that, for example, in one of Routledge’s key book series on nations of the Middle East (South Yemen, A Marxist Republic, Robert W. Stookey which has been published three times to date) Haines is mentioned in only four sentences. Neither is Haines lauded in contemporary Britain as being a great figure in British Imperial history. [1] A communique from the Chief Secretary to the Government of Bombay to the Foreign Secretary to the Government of India dated 29 October 1936 bluntly decided that: “altogether, the history of Captain Haines is a matter for pity rather than for pride, and it is better that it should not be commemorated”.[2] Thirteen years earlier in 1923, the Political Agent of Aden (Major-General T.E. Scott) was given the exact same reasoning by Sir Ernest Hotson writing from Mahabaleshwar in India as to why remembrance of Captain Haines should be stifled. On the face of it, this strikes as a stark betrayal of a man who served in the Royal Indian Navy from around the age of eighteen, spent years on instruction surveying the south coast of Arabia, who carried out the difficult task of trying to negotiate Aden’s surrender, who was, in fact, also a learned scientist and artist and who gave another fifteen years of his life to developing that place that the Irish noble, Lord Valentia, described as the Gibraltar of the East, Aden.[3] Haines himself described Aden as “a child of my own adoption” and that he would always “feel a deep interest in the welfare and well doing of all there”.[4]

Letter by Sir Hotson, 1923

Captain Haines’ fall from grace into ignominy began on 26 August 1854, when he was arrested by the Sheriff of Bombay and imprisoned in Mazagon jail. The cause was an approximate missing £3.5 million in today’s valuation of British sterling (£28,198 in the 1850s) from the Aden Treasury. The deficit had been discovered in September 1852. Four months earlier the Account General of the Government of Bombay had decided to check the Aden Treasury, a staggering thirteen years after Aden had come under imperial control when the checks should have been done once a month since 1839. The checks, once finally done, and a subsequent Commission revealed not only the missing money but also Haines’ somewhat bizarre financial handling practices. For instance, Haines admitted to allowing merchants to exchange rupees for Maria Theresa dollars (the currency of the Habsburg Empire) and allowed them to reclaim the rupees. Rupees at this point were not even accepted for inland trade as it was a new currency and only the Maria Theresa dollars were used. He also used a banker (by the name of Damjee) without having informed the Government of Bombay and from whom he secured advances. Haines further offered loans to his staff and to property developers (once to improve an Aden hotel despite the fact it was public money). The Commission discovered that the accounts were all in Gujarati even though this language was not commonly known to all. The report of the Commission headed by Major Scobie and Mr Archibald Robinson was submitted to the Government of Bombay who determined that Haines had committed fraud. On 22 February 1854 he was told he was no longer Political Agent of Aden and ordered to face the Government in Bombay. This must have come as a complete shock to the fifteen-year virtual dictator of Aden and who had honestly believed that he would only be criticised over the missing money. He referred to this as a ‘wigging’, a word that now only belongs to archaic English. Haines was a Master of Political Management and military strategy but the financial affairs of Aden betrayed his immaturity in such matters (despite the serious charges against him he arrived in Bombay in April 1854 with 49 pairs of trousers, 33 new shirts and 13 pillowcases amongst many other elaborate effects) and stripped him of his power.[5]

Discussion of Captain Haines is normally in dry terms: he was a man of fifteen years successful service in Aden as an Administrator and Political Representative, the founder of the first outpost of the British Empire acquired in the reign of Queen Victoria of such importance in British sea communications with the East.[6] Whilst this is all true, it hides who else he was. He is also sometimes mischaracterised as a “swashbuckler”.[7] Records show that it was Captain Smith, Captain J.M. Willoughby and Major T. Bailie who headed up the combined force of soldiers and sailors who stormed Aden not Haines. They used brass and iron guns where four were killed and ten wounded on the British side (among them one Bhistie, from the Muslim Indian tribe that claim descent from Abbas ibn Ali). Smith, Willoughby and Bailie might have executed the required military operation but what Haines did was to take care of the required political management of Aden. On 22 January 1839, Haines wrote to the Secretary of the Government of Bombay to report that his first actions were to “encourage the inhabitants of Aden in their usual occupations”, to write to the Sultan Houssain and Hamed, as well as the Chieftains of the Hazzabee [Al-Uzaibi], H.Agrabee [Al-Aqrabi] and Honshabee [Al-Hawshabi] Tribes offering medical assistance and free exchange within Aden. The same letters states that these efforts were “quite successful and that the Chieftains of the Tribes all expressed an attitude of peace towards him, sending supplies and camels for the Government stores. His third action was to write to different coastal ports, informing that Aden was free for trade as a British port.[8]

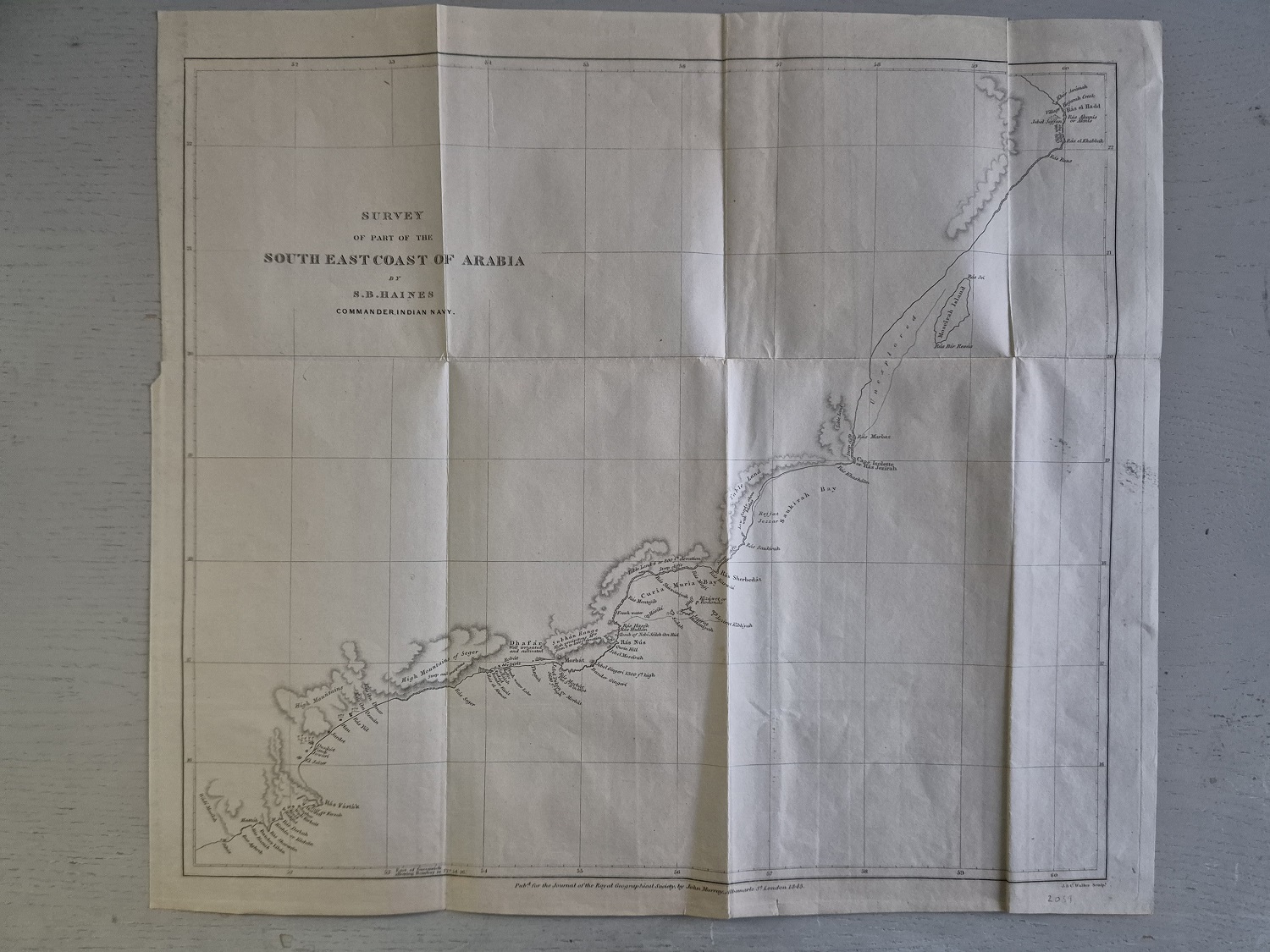

Quite apart from the popular view of empire builders as adventurers, Haines was well versed in science and art. Namely, he was engaged in applied science and cartography. Haines provided geographical research to The Bombay Geographical Society (tidal and meteorological observations).[9] Haines created and assisted in creating numerous maps from as early on as 1828. In 1828 he carried out a survey which required expertise in hydrography of the coast of Arabia using the principles of trigonometry to create a network of points from Ras Goberhindee to Ras Soaote.[10] A further survey of the entrance to the Gulf of Persia and Coast of Arabia from Ras Goberindee to Mucat was completed in 1828 and published in 1831.[11] Later, in 1835, another trigonometrical survey, this time of Socotra by Haines, was published by James Horsburgh, Hydrographer to the East India Company. This contains an inset map detailing Samhah and Darsah Islands, with notes about vegetation, the terrain and the location of “Bedouin caves” as well as water depth represented by soundings (numbers).[12] A study of a map Captain Haines made in 1850 quickly reveals that he was a fine draughtsman and capable of creating terrain cartography. The 1850 relief in ink on tracing cloth of the south western part of the Arabian Peninsula from Hodeidah to Wady Meifah by Haines uses hachures to show the steepness of terrain, it also contains information concerning agricultural production and information of where various tribes held power.[13] In 1845 the Royal Geographical Society published an engraved map by Haines that was a survey performed in 1839 of part of the South East Coast of Arabia (pictured).This was important because his survey of this area had never been recorded or charted before and the map itself shows one area marked as “Unexplored”. Hachures are indicated as with his other maps and villages as well as freshwater lakes including irrigated land are marked out. The map stretches from Wadi Masilah to Jebel Saffan, and shows Masirah Island and Khuriya Muriya Bay (Oman). The map pre-dates the opening of the Suez Canal (1869) by more than two decades and as such is a rare primary source. The author recently purchased it from an antiquarian bookseller in Vienna who holds other rare sources connected to Captain Haines. The maps of Captain Haines are both important scientific calculi and beautiful artefacts. Critically, Captain Haines’ rapacious knowledge production seems to sit somewhere between Edward Said’s claim in Orientalism that British knowledge acquisition in the 19th century was inseparable from the act of imposing imperial power and Robert Irwin’s claim in For Lust of Knowing: The Orientalists and Their Enemies that it stemmed from a shared obsession for scholarship: “An increasing number of scholars more generally have come to accept that knowledge is socially constructed and that complex developments contribute towards shaping our understandings of the world”.[14]

Survey of Part of the South East Coast of Arabia, published 1845

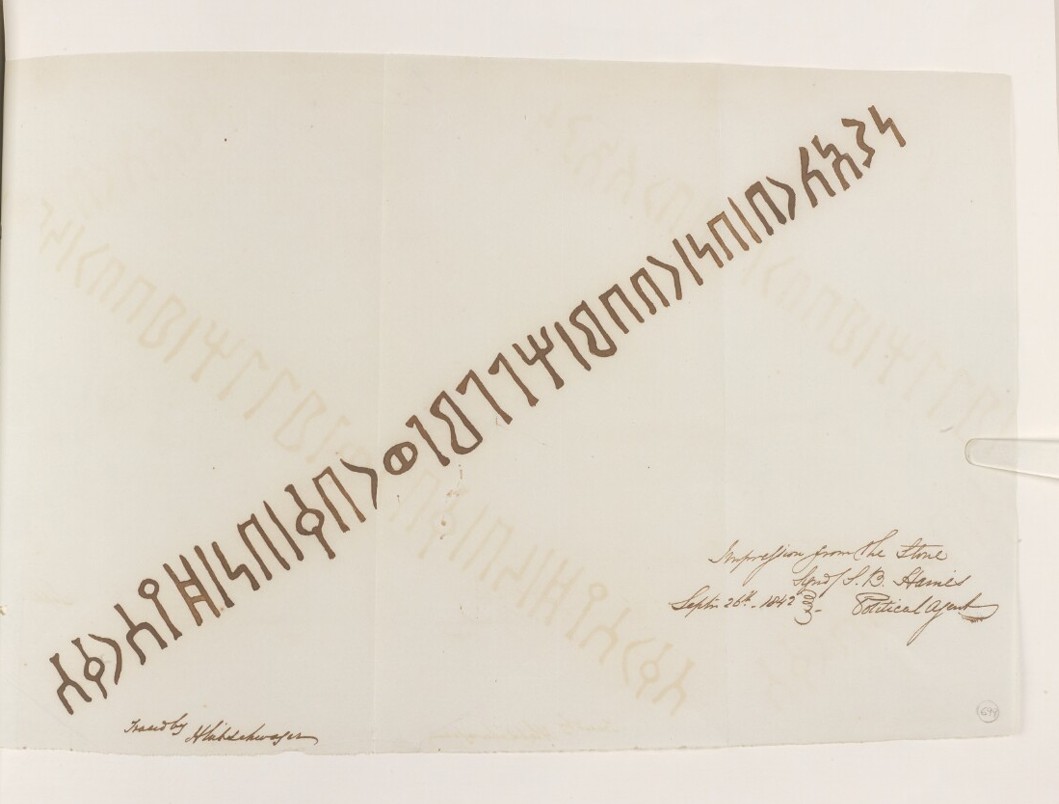

Haines also took great interest in any antiquities found in Aden. Upon the occasion of the Executive Engineer at Aden, Lieutenant John Adee Curtis, discovering ancient South Arabian script (Himyaritic) on a piece of well-cut polished stalactitic marble as well as what are described as 7 “gold Mahomedan coins” initially thought to be 340 years old, Haines, dabbling in the methods of an archaeologist, made a copy of the Himyaritic inscription which he sent with a letter to the Government of Bombay on 29 September 1842. The marble was ordered to be packed and sent to the Persian Department in Bombay and the gold coins were also sent. Information about the antiquities was sent to the Royal Asiatic Society and the Persian Department translated and transliterated the only coin that could be deciphered (There is none but God and his prophet Mahomed and Sultan The King The Noble 1125). Haines was directed on 14 November 1842 to send any further similar antiquities found in Aden.[15]

Copy of an inscription of ancient Himyaritic by Captain Haines, 1842

Not content with just engaging in natural philosophy, art and archaeology, Haines also wrote a history in 1845, entitled History of the Present Family of Lahej. In John M. Willis’ Making Yemen Indian which is primarily concerned with challenging the postwar concept of the Middle East in relation to South Yemen, it is reported that the narrative Haines created became the institutionalised history of Lahj. The narrative traces the history of the Abdali sultanate. Willis notes that Haines drew a comparison between Britain’s medieval past and Lahj’s past by referring to the Abdali dynastic chronicle (Da’ira) as the Doomsday Book suggesting political evolution toward a modern state. Willis goes on to claim that Haines placed great emphasis on the year 1141 AH (1728 CE). In this year, according to Haines, Sultan Fadl bin Ali al Abdali repelled the suzerainty of the North Yemen Zaydi imamate and founded an independent polity in Lahj and Aden. Willis states that the weight given to this year by Haines was in order to depict British rule as a natural succession from the Abdali dynasty (that it was merely power transfer) and further that the British were preserving the “nine tribes” who allegedly participated in a liberation movement against northern control beginning in 1728.[16]

“Haines himself never left his house [in Aden] without two pistols in his belt”.[17] Despite Haines’ administration of Aden for multiple years as his own fiefdom [18] his position was never fully secure. Initially, James Rivett-Carnac (Governor of the Bombay Presidency 1838 - 1841) did not wish to see Aden as a permanent British settlement. The troops stationed at Aden were not put under the control of Haines and the division of power often put him at bloody odds with the military. First he fought with Major Bailie just six months after the occupation. Then, he fought Colonel Capon who had replaced Major Bailie. There were further flare ups between the political and military powers at Aden, in 1841, 1846 and 1847. The pre-eminent historian, R.J. Gavin, remarks that Captain Haines was very sensitive to any personal insult which is attested to in his personal letters and this along with his ramshackle administrative system plus his belief that Aden belonged to him provoked one crisis after another with the garrison.[19]

Despite facing challenges from the military wing in Aden, Haines’ political supremacy was assured in Aden due to his alliance with Arab elites. Haines could speak Arabic (he could also read Hebrew) and never kept Arabs at a distance, preferring them to the company of Europeans. He opted to fully engage with the political dramas that played out in the Arab sphere of Aden. Haines established a network of Arab (and Jewish agents) who brought him reliable information from the interior of Aden, from the hinterland of South Yemen and also from North Yemen. Working with the Arab business community, Haines was able to exercise a great amount of power and ensure their loyalty in return. He too was said to have shown incredible loyalty to his Arab coterie: “He showed a decided preference for the cosmopolitan Arabs of the coast – the men of every country and of none, men untied by tribal traditions and sceptical of religious beliefs. These were the men Haines liked and trusted”.[20] It is interesting to note in contrast how the late Professor C. E. Farah (Professor of Middle Eastern Studies, University of Minnesota), presents Haines in terms of his character referring to him as bullish, devious and arrogant, a characterisation that seems conspicuously coloured by overt value judgements.[21] The view of Professor Farah is further contradicted when Captain Haines’ (successful) attempt to keep Aden under civilian rather than military control is considered. In February 1840 Colonel Capon launched a series of raids against the Aden bazaar in an attempt to discover unlicensed distilleries and illegal liquor, arguing that he had jurisdiction over the bazaar as the whole of Aden settlement was a military camp. Haines received a flurry of complaints such as when Gorleb bin Mawger bin Hamed informed him that a sepoy (Indian soldier) in the Bazaar Guard had hit him with his fist and had brandished his musket at him even though bin Hamed was only standing and talking by Ibrahim the Jew’s shop. Haines referred the whole matter to the government in Bombay and won its support for keeping Aden under civilian control.[22] Haines even proved himself to be sensitive to the religious practices common to Aden. By March 1839, which was only weeks since the British occupation began, Haines permitted the ziyara of Sayyid Aydarus to be observed. Ziyara is a festival celebrating the death anniversary of a Sufi saint. Famed Adeni historian Hamza Luqman listed fourteen mosques in historical Aden in his Tarikh Adan, some of which had the tombs of saints dating back to the Middle Ages which indicates Haines was alive to the spiritual history of Aden in allowing ziyara. Haines reported that thousands of Sufis attended the Sayyid Aydarus ziyara.[23]

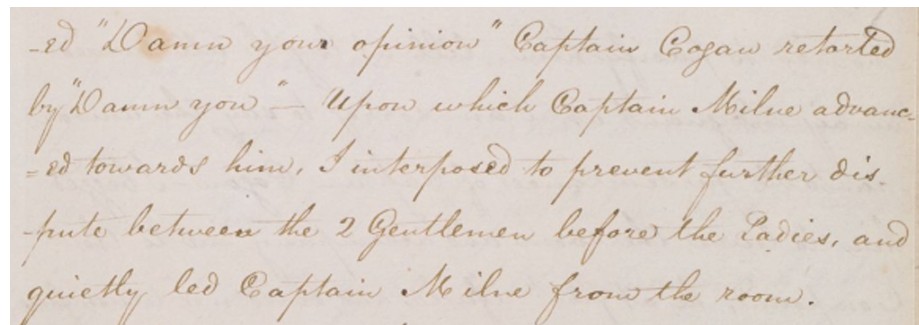

Speaking to Haines’ lived experience as Political Agent of Aden, during which he never took leave in fifteen years except once when he was ill, and outside of his conflicts with the garrison, Haines’ sensitivity also cost him a 30 year friendship. On 27 October 1846, Haines was having dinner with a Captain Robert Cogan who had recently retired from the Indian Navy to settle in Aden and a Captain George James Duncan Milne. At one point in the evening, Cogan insulted Haines’ wife (Mary). A heated argument broke out with Milne exclaiming to Cogan “damn your opinions” and Cogan replying “damn you”. This exchange nearly resulted in Milne launching a physical attack on Cogan which Haines had to prevent so the ladies present would not have to witness this. Haines was then called a cold blooded being by Cogan. Haines eventually ensured that everyone returned to their own homes and as he was also a magistrate in Aden, he ordered a policeman to put Cogan under surveillance with further orders to not let him leave his home that night. The next morning Haines received a message from Cogan who although regretted his behaviour insisted that Haines was “irritating”. This caused Haines to reply with a message severing his friendship with Cogan forever. Cogan was then arrested in error when he attempted to leave his home. The arrest was investigated when Cogan complained to the Governor in India. The Government of Bombay ultimately found that Haines was in the right to prioritise the peace in Aden by curbing Cogan’s movements and sadly Cogan died the next year.[24]

Captain Haines’ record of the squabble between Cogan and Milne

Counter to the claims of the decolonisation movement prevalent in UK academia which sees the story of the British Empire as a story of racism and oppression are records that reveal Haines, acting as a magistrate in Aden, was active in the effort to put slavers on trial.[25] Long before the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in Britain in 1833, the India Act established a new Board of Control in 1784 to supervise the activities of the East India Company and enact measures to protect children from falling into the hands of slavers. In one such case, Haines had provided information to J H Patton, Chief Magistrate of Calcutta that a slave child called Nusseeb was on board a ship called the Aden Merchant in the port of Calcutta. Patton investigated the matter in November 1843 and Nusseeb is said to have denied being a slave. Haines however would not accept this denial. He was completely convinced that the supercargo of the ship Aden Merchant, Ali Abdullah, was in fact a slaver whom others were frightened to testify against and Haines’ anger at the situation as he judged it led him to write to the Secretary to the Government of Bombay stating that all of Aden knew Ali Abdullah to be a slaver. This letter led to Haines being given permission to carry out a full enquiry into Ali Abdullah once he returned to Aden. Ali Abdullah returned but Nusseeb was missing (it was later discovered that he had been sent to Jeddah along with other alleged victims of slavery). Ali Abdullah refused to answer Haines’ questions, only stating that he was the “son” of Haines and had nothing more to say. Haines persevered and put Ali Abdullah on trial as a slave dealer. Although the eventual verdict was that the charge was not proven due to a lack of witnesses and the case was dismissed by August 1844 it does appear that “the same Christian, humanitarian, ‘improving spirit’ [26] that had taken a hold of British government in India was also in effect in the person of Captain Haines given his copious efforts to bring a suspected slaver to justice. This spirit of improvement for the situation in Aden accords with the contents of his memoir in which he recalls that two and a half centuries prior to British occupation, Aden, was among the foremost of commercial markets of the East, a legacy that stretched back to the 4th century AD.[27]

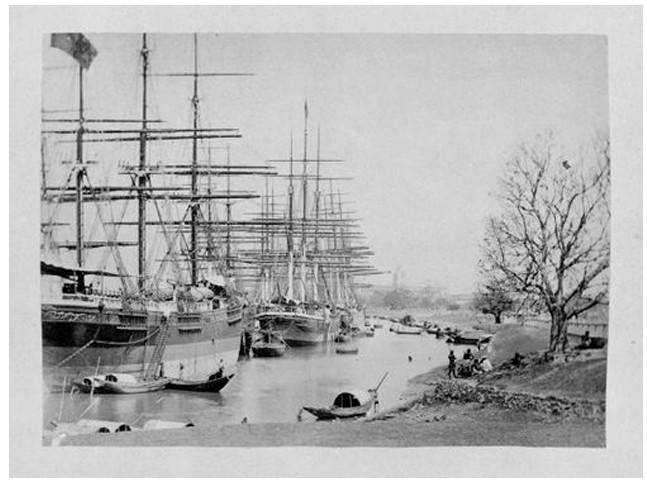

Banks of the Hooghly, Calcutta, 19th century

Having had arrived in Bombay in April 1854, Haines was quickly made to face the judgement of the Supreme Court of Bombay. First, in July 1854 when he was tried by jury on twenty two counts charging malversation and embezzlement between 01 March and 01 September 1852. His barrister was Mr Geoffrey Taylor and he pleaded ‘Not Guilty’ before Judge Sir Charles Jackson. Despite many witnesses having been brought from Aden to testify for the prosecution, such as Ali Bu-Beker an Arab merchant, the jury returned a ‘Not Guilty’ verdict. In August 1854 he was subjected to his second trial (also before Judge Jackson) but was also found to be ‘Not Guilty’. Haines stated later in a letter that cheering had rung out in the Court and along the whole street at both verdicts being read out. The joy felt at the verdicts that acquitted Haines was followed by tragedy. The Government of Bombay would not accept either verdict and so converted the criminal case into a civil action, demanding the huge sum of missing money from Aden Treasury be returned. Haines attempted a settlement offer which included his property in Aden and abroad except he wished to retain his collection of stuffed birds, his wife’s jewels and a sword presented to him in January 1839. The Government of Bombay accepted this offer but Haines then made a terrible blunder: he withdrew his offer because the Government had explicitly stated that the settlement would not indicate that it no longer considered him to be guilty. The civil case was concluded in just fifteen minutes on 04 January 1855 and upon it being decided that Haines owed the East India Company (£28,198) he was arrested and jailed. Later, he was removed from the list of the Indian Navy and his property in Aden was sold. For a time Haines was given temporary release from jail by being discharged to the custody of the Sheriff of Bombay for serious physical and mental health reasons (though he was watched constantly even while he ate and slept). By August 1855, the Government of Bombay attempted to allow him to return to England or at least live freely in Bombay. The East India Company refused to allow this. Imperial historian Gordon Waterfield calls this a “stupid and wicked decision, amounting to a sentence of death”.[28] Haines twice appealed to be released from the custody of the Sheriff of Bombay but both appeals were dismissed. He was finally shown mercy when Sir George Clerk the new Governor of Bombay ordered his release on 09 June 1860 after reading what was Haines’ fifth petition but he died in Bombay harbour on board the Poictiers suffering with amoebic dysentery on 16 June 1860. His body remains in India buried at the Colaba Church cemetery. [29]

The history of Captain Haines is a matter for…admiration and sorrow. I write this because pity implies a level of superiority and pride in this context is delusional. The British were driven to occupy Aden out of fear of French and then Egyptian expansion and the success of the occupation cut their access to the western approaches of British India.[30] It was not necessary that there had not been a “great feat of arms” [31] in the capture of Aden. The endeavours of Captain Haines simultaneously eliminated these threats whilst transforming Aden into a thriving entrepôt and there is little pride to be found in a strategy developed out of fear. It is almost undeniable that Captain Haines was a self made cultured and highly intelligent man deserving of admiration. His fate was a bitter drink as acknowledged in an epitaph by a local Bombay newspaper:

A dark chapter in the history of the Bombay Government has at length come to a conclusion. A gloomier page, indeed, will scarcely be found anywhere, except, perchance, in the records of Neapolitan misrule. A mere debtor – if, indeed, he were that – had been for nearly six years confined in jail, in a deadly climate, at the suit of the Government he had served with pre-eminent zeal and ability. What more could have been done to him had he actually been found guilty of the fraud and embezzlement which were so strenuously charged against him? …His power no one disputed, for no one denied that it was justly and wisely exercised. …But Captain Haines, though an excellent administrator, was an indifferent book-keeper. Probably he knew nothing of double entry, and was no better acquainted with finance than financiers usually are with navigation. …Repeatedly did the Political Agent urge his worshipful masters to place the financial department upon a larger and securer footing. It was all in vain. They were busied about many things and had no time to spare a thought upon the burning rock of Aden… [32]

1- Edwards, Aaron, “Mad Mitch’s Tribal Law – Aden and the End of

Empire”, Transworld Publishers, London, 2014, Introduction.

2- PZ 5179/36 'Aden: proposed memorial to Captain S. B. Haines,

R.I.N.', British Library: India Office Records and Private

Papers, IOR/L/PS/12/206, in Qatar Digital Library <https://www.qdl.qa/archive/81055/vdc_100000000466.0x000211>.

3- George, Viscount Valentia, “Voyages and Travels in India, Ceylon,

the Red Sea, Abyssinia, and Egypt, in the years 1802, 1803, 1804, 1805, and 1806”, W. Miller, London, 1809.

5- Waterfield, Gordon, “Sultans of Aden”, Stacey International, London, 2002 edition, pp 206 – 213.

6- PZ 5179/36, Loc. cit.

8- PZ 5179/36, Loc. cit.

9- 'Transactions of the Bombay Geographical Society, from May 1849 to

August 1850. Edited by the Secretary. Volume IX.' [112] (131/504), British

Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, ST 393, vol 9, in Qatar

Digital Library https://www.qdl.qa/archive/81055/vdc_100099766223.0x000084.

10- Trigonometrical Survey of the Coast of Arabia, from Ras

Goberhindee to Ras Soaote, by Commander G.B. Brucks & Lieutenant S.B.

Haines, H.C. Marine, 1828. Engraved by R. Bateman, 85 Long Acre’ [13r] (1/2),

British Library: Map Collections, IOR/X/3630/18, in Qatar Digital Library

11- ‘The Entrance to the Gulf of Persia; and Coast of Arabia from Ras

Goberindee to Muscat. Surveyed by Com.r G.B. Brucks, and Lt. S.B. Haines, H.C.

Marine, 1828. Engraved by Richard Bateman’ [12r] (1/2), British Library: Map

Collections, IOR/X/3630/17, in Qatar Digital Library

12- ‘A Trigonometrical Survey of Socotra by Lieut.ts S.B. Haines and

I.R. Wellsted assisted by Lieut. I.P. Sanders and Mess.rs Rennie Cruttenden

& Fleming Mids.n, Indian Navy. Engraved by R. Bateman, 72 Long Acre’ [8r]

(1/2), British Library: Map Collections, IOR/X/3630/13, in Qatar Digital

Library

13- A map of the south-western part of the Arabian

Peninsula, from Hodeidah to Wady Meifah [1r] (1/2), British Library: Map

Collections, IOR/X/3219, in Qatar Digital Library

14- Ansari, K. Humayun, “The Muslim World in British Historical Imaginations: ‘Rethinking Orientalism’”?, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Vol. 38, No.1 (April 2011), 1, p.73.

15- ‘Aden. Regarding Hymyaritic [Himyaritic] Inscriptions and Ancient Coins found at Aden’ [694r] (13/40), British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, IOR/F/4/2005/89508, in Qatar Digital Library

16- Willis, John M., “Making Yemen Indian: Rewriting the Boundaries of Imperial Arabia”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol.41, No.1, February 2009, pp.28-29.

17- Gavin, R. J., “Aden Under British Rule 1839 - 1967”, Barnes & Noble Books, New York, 1975, p.60.

18- Reese, Scott S., “Imperial Muslims: Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937”, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2018, p.163.

19- Gavin, Op. cit., pp.39-44.

20- Op. cit., p.45.

21- Farah, Caesar E., “The British Challenge to Ottoman Authority in Yemen”, Turkish Studies Association Bulletin, Vol.22, No.1, Spring 1998, pp.36-57.

22- Scott, Op.cit., pp.115-116.

23- Scott, Op.cit., p.127.

24- Courtney, Anne, “‘An unseemly squabble’ in Aden”, Untold lives blog, British Library, India Office Records, 09 September 2021.

25- O’Brien, John, “The Slave Trade at Aden, Part 1 & 2”, Untold lives blog, British Library, India Office Records, 18 November 2014, 20 November 2014.

26- Biggar, Nigel, “Colonialism, A Moral Reckoning”, William Collins, London, 2024, p.29.

27- Haines, S. B., “Memoir to accompany a chart of the South Coast of Arabia from the entrance of the Red Sea to Misenat”, The Royal Geographical Society, London, 1839-1845, p.135.

28- Waterfield, Op.cit., p.237.

29- Waterfield, Op.cit., pp.225-241.

30- Stookey, Robert W., “South Yemen A Marxist Republic in Arabia”, Routledge, New York, 2019 edition, p.31.

31- PZ 5179/36, Loc.cit.

32- Allen’s Indian Mail, 06 August 1860 as cited in Waterfield, “Sultans of Aden”.