Image: A traditional market in Aden, South Yemen, February 21, 2024 (South24 Center)

آخر تحديث في: 08-01-2025 الساعة 11 صباحاً بتوقيت عدن

|

|

Despite Yemen’s instability, the private sector drives economic resilience. However, political fragmentation and revenue losses hinder recovery, requiring reforms and diaspora investment for sustainable growth.

Rania Walid Khyali (South24 Center)

Can economic development be a realistic discussion amidst Yemen’s ongoing political and economic uncertainty? The answer is a definitive Yes. Despite its challenges, Yemen’s economy has demonstrated resilience and dynamism, reflecting the adaptability often seen in post-conflict markets. These markets are inherently dynamic, shaped by regulations, cultural norms, and societal practices[1]. Yemen’s economy, despite its challenges, reflects this dynamism, presenting opportunities for recovery and growth.

Private Sector Dominance and Regional Disparities

Despite the instability, the Yemeni market has shown resilience and adaptability. Since 2016, economic activities have evolved to align with the country's new economic structure. The private sector, for instance, now contributes approximately 70% to Yemen’s GDP - a significant increase compared to the pre-war period - emerging as a cornerstone of essential services and economic development amidst the dysfunction of public institutions [2].

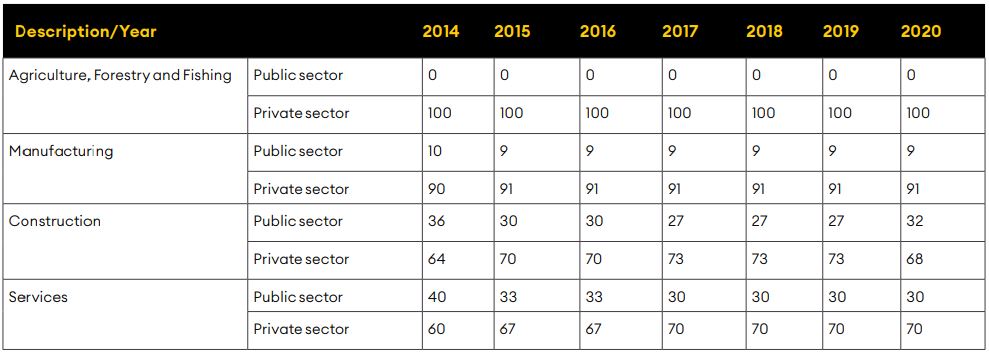

Table (1): GDP by productive and services sector for the private sector in 2020

The data is sourced from the Central Statistical Organization’s Statistical book of 2020, as illustrated in a report by Economic Development Initiatives[3]

The table shows that the private sector dominates all industries, particularly agriculture, forestry, and fishing with a 100% contribution. This is followed by its significant role in manufacturing 90–91%, construction 64–73%, and services 60–70%.

Most enterprises are small or micro in scale, with large enterprises comprising just 3.6% of the total. Medium and large enterprises are concentrated in Sana’a, where they represent 41% and 36%, respectively. By contrast, these figures are significantly lower in Aden, at 13% for medium enterprises and 22% for large enterprises, and in Hadramout, at 18% and 11.6%, respectively[4]. This regional disparity is unsurprising. Even before the war, manufacturing activity between 2008 and 2012 accounted for only 3% of GDP in Aden compared to 19% in Sana’a. This imbalance can largely be attributed to the centralization of policymaking in Sana’a, despite Aden’s strategic geographic location [5].

The power imbalance between Aden’s Internationally Recognized Government (IRG) and the Houthi-led government in Sana’a, combined with Aden’s limited authority, has exacerbated the macroeconomic instability in areas under the control of the legitimate government. These dynamics have fostered uneven development deterring businesses, particularly those led by Yemeni diaspora entrepreneurs - from entering the market and contributing to economic recovery and growth [6].

A key example is the experience of Somaliland, where the absence of centralized control allowed the private sector and diaspora to drive economic development and peacebuilding[7]. In contrast, Yemeni diaspora investors remain hesitant to engage in the Yemeni market due to persistent political and economic instability[8]. Barriers such as restrictive port access imposed by the Houthis and illegal fees at security checkpoints further inflate production costs and delay deliveries, undermining market efficiency [9].

Coping Mechanisms and Youth Self-Employment

Amid these challenges, Yemeni communities have developed coping strategies to navigate the economic hardship. The World Bank Economic Monitor of 2023 reported a modest GDP recovery, largely driven by increased government and household expenditures[10]. Remittances and international grants play a significant role, but the growing culture of youth self-employment and entrepreneurship has also emerged as a vital driver of economic resilience.

Many individuals have turned to small businesses and informal trade to survive, showcasing adaptability and ingenuity. Social media discussions highlight how small businesses have become a vital coping mechanism for managing rising costs and supporting livelihoods in Yemen [11]. While the relationship between increased household expenditure and self-employment in Yemen remains underexplored, similar trends in Rwanda reveal promising outcomes. There, youth self-employment has been linked to improved household spending, job creation, and human capital development.[12]

Despite their potential, youth-led enterprises in Yemen are constrained by systemic barriers, including inflation, limited access to capital, and the high costs of operating in an unstable economy. Additionally, self-employed youth are hesitant to take loans due to the risks posed by Yemen’s volatile macroeconomic environment, and youth entrepreneurs fear that business failure could leave them burdened with debt. These challenges are compounded by systemic issues within Yemen’s financial sector, which further limit opportunities for youth entrepreneurs.

Between 2011 and 2019, Yemen’s banking sector remained underdeveloped, with assets and deposits accounting for just 15.4% of GDP. Liquidity constraints, firms’ preference for cash transactions, and the lack of robust credit reporting, enforcement mechanisms, and bankruptcy laws hindered financial growth. As a result, many large businesses resorted to informal financial networks rather than formal intermediaries[13].

Despite these challenges, promising developments are emerging. In September 2023, an employee at Al-Qutaibi Bank in Aden highlighted the adoption of digital banking as a transformative step [14]. Since transitioning from an exchange company to a formal bank in 2021, Al-Qutaibi has leveraged its reputation for trust and flexibility to integrate informal practices, such as WhatsApp-based transactions, into a formal digital system[15]. Digital banking is becoming increasingly normalized in Aden, streamlining transactions, improving accessibility, and fostering financial inclusion. While significant challenges remain, these advancements lay the groundwork for a more resilient financial sector.

Challenges and Lack of Agency

The stability of Yemen’s local currency and economy remains highly dependent on oil and gas revenues, which fell by half in 2023. This decline worsened in early 2024, with revenues dropping another 42% due to export suspensions. The situation was further exacerbated by a 34.5% decline in customs revenues as imports increasingly shifted to Hodeidah port, controlled by the Houthis. These disruptions have strained public services and delayed the payment of public sector salaries[16]. leaving the economy heavily reliant on international aid to prevent a currency collapse[17].

In February 2024, the Central Bank of Yemen - Aden (CBY-Aden) introduced measures to regulate the financial networks, including money transfer systems and exchange offices operating in Houthi-controlled areas. These reforms aimed to curb currency speculation and combat illegal financial practices, which have destabilized the Yemeni remittance and transfer system [18].

Tensions escalated when the Houthi-governed Central Bank in Sana’a minted new 100-rial coins, a move that could generate additional funds for the militia’s operations while circumventing existing sanctions [19]. This action was perceived by CBY-Aden as a direct challenge to its legitimacy. In response, CBY-Aden issued a directive requiring all banks in Sana’a to relocate to Aden. Non-compliance, it warned, would result in exclusion from global financial networks like SWIFT, Western Union, and MoneyGram. [20]

The directive was condemned by the Sana’a-based Yemeni Banks Association [21], while the Houthis immediately issued military threats targeting Saudi Arabia and the government. These developments prompted Saudi Arabia to intervene, resulting in the suspension of CBY-Aden’s measures[22]. The inability of Aden’s government to assert authority over key economic and administrative functions has hindered its ability to lead effective recovery efforts. Persistent political fragmentation and governance challenges continue to erode public trust and economic stability.

A recent discussion among world development economists, including Paul Collier, emphasized the importance of people’s agency for achieving sustainable development, which entails boosting the capacity of local communities and institutions to effect change and create an environment conducive to growth [23]. Unfortunately, the lack of effective government agency in Aden has hindered efforts to improve the livelihoods of its citizens. Similarly, attempts by the Central Bank of Yemen-Aden (CBY-Aden) to stabilize the nation’s macroeconomy have been consistently undermined.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Despite Yemen’s political and economic challenges, opportunities for economic development remain. The resilience and adaptability of the private sector, coupled with community-level enterprises and advancements in financial infrastructure, underscore the potential for growth in a post-conflict environment.

However, doubts persist regarding the future of economic recovery in the absence of Aden’s government’s capability to alleviate the economic hardships of its citizens, stabilize the economy, and foster equitable development– that continues to hinder progress. Building trust among investors - particularly the Yemeni diaspora - will be pivotal to achieving sustainable recovery and addressing the disparities discussed earlier.

In response to these challenges, initiatives that must be prioritized include the resumption of oil and gas exports from IRG ports and the restoration of customs revenues to stabilize the economy and ensure the payment of public sector salaries. These measures will, in turn, reduce dependency on international aid, strengthen purchasing power, stabilize the economy, and enhance the value of the Yemeni rial against the dollar.

[1] Tracey Gustle and Laura Meissner. Practice Note 1: Market development in conflict-affected contexts. International Alert. Accessed from: international-alert.org

[2] Economic Development Initiative. Unlocking the Potential of the Private Sector in Yemen. HSA Group, 2023. Accessed from: hsayemen.com

[3] Ibid

[4] Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation. Promoting Partnership with the Private Sector: Private Sector Contributions to Strengthening Socio-Economic Resilience (Community) - Partnership Prerequisites, Challenges, and Remedies. Yemen Socio-Economic Update, Issue 53, October 2020.

[5] Ammar Aamer. Manufacturing in Yemen: Challenges and Obstacles. Academic Journal of Research in Economics and Management, Vol. 7,pp. 119-142, 2015. Accessed from: researchgate.net

[6] Observations from Informal Discussions. Based on informal discussions with business owners residing in Saudi Arabia, who shared that conducting business in Aden is perceived as unsuccessful due to ongoing economic and political instability.

[7] Ahmed M. Musa, and Cindy Horst. State formation and economic development in post-war Somaliland: the impact of the private sector in an unrecognised state. Conflict, Security & Development, Vol. 19(1), pp. 35–53. 2019. Available at: doi.org

[8] Based on informal discussions with business owners residing in Saudi Arabia, who shared that conducting business in Aden is perceived as unsuccessful due to ongoing economic and political instability

[9] Federation of Yemen Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Indicators of the Performance of the Industrial Sector in Yemen in light of Conflict and War. Available at: fycci-ye.org

[10] The World Bank. Yemen Economic Monitor: Peace on the Horizon? Fall 2023. Available at:documents.worldbank.org

[11] Social Media Observations. Based on informal discussions on social media platforms, where self-employed individuals in Yemen highlighted how their work enables them to manage expenses and provide for their families amidst ongoing economic challenges.

[12] Dr. Jean Paul Mpakaniye. The Impact of Youth Self-Employment Behavior on Socio-Economic Development in Rwanda. October 2017. Available at ssrn.com

[13] Sherilyn Raga, et al. Impact of conflict on the financial sector in Yemen: implications for food security. Working paper, December, 2021. Available at: odi.org

[14] Rania Walid, A New Analytical Approach to Money Exchange Companies (Hawala): A Case Study of Informal Money Transfer in South Yemen. Diss. London (SOAS), University of London, 2023. [Unpublished].

[15] Ibid

[16] The World Bank. Yemen Economic Monitor: Confronting Escalating Challenges, Fall 2024. October 2024. Available at: documents1.worldbank.org

[17] Reuters. Arab Monetary Fund Signs $1 Billion Agreement to Support Yemeni Government Reforms – Saudi State Media.November 27, 2022. Available at: reuters.com

[18] Scope 24. The Central Bank Stops Money Transfer Through the Network of Exchange Companies. February 19, 2024. Available at: scope24.net

[19] United Nations Security Council. Final Report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen Established Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2140 (2014). October 11, 2024. Available at: documents.un.org

[20] Central Bank of Yemen-Aden. Central Bank Governor Decision No. (30) of 2024 Concerning Licenses of Banks [Arabic]. July 8, 2024. Available at: sahaafa.net

[21] Saeed Al-Batat. Yemen’s Central Bank Revokes Licenses of 6 Sanaa Banks. Arab News, July 11, 2024. Available at: arabnews.com

[22] Office of the UN Special Envoy for Yemen. Statement by the Office of the UN Special Envoy for Yemen. July 23, 2024. Available at: osesgy.unmissions.org

[23] Paul Collier. Left Behind: A New Economics for Neglected Places. Penguin Book, 2024.

قبل 3 أشهر